Share This:

Raise your hand if you have ever given children the assignment to “sort and write” their words. (Me!)

Raise your hand if you have ever asked children to write a word 3 times each. (Also me!)

Last one friends. Raise your hand if you have ever had children sort and glue their words in at the end of the week. (I’m out of hands, or I’d be raising another one).

As part of my master’s degree in reading, I took a course in word study. I live in Virginia, where Words Their Way originated, and I felt like I was on the cutting-edge of word study instruction. Bye-bye whole group spelling tests, HELLO individualized word sorts for each small group. We were elbow deep in word sorts and word sorting activities. At the time, I thought I was doing what’s best for children. I strongly believed in using word sorts.

Looking back, despite having an entire word study course, I was not trained in the actual phonics of English and how that translates into instruction for our students. Today, I know better and so I do better. So let’s take a look at some old practices, why the traditional word sort approach doesn’t work, and how we can alter them for today’s instruction.

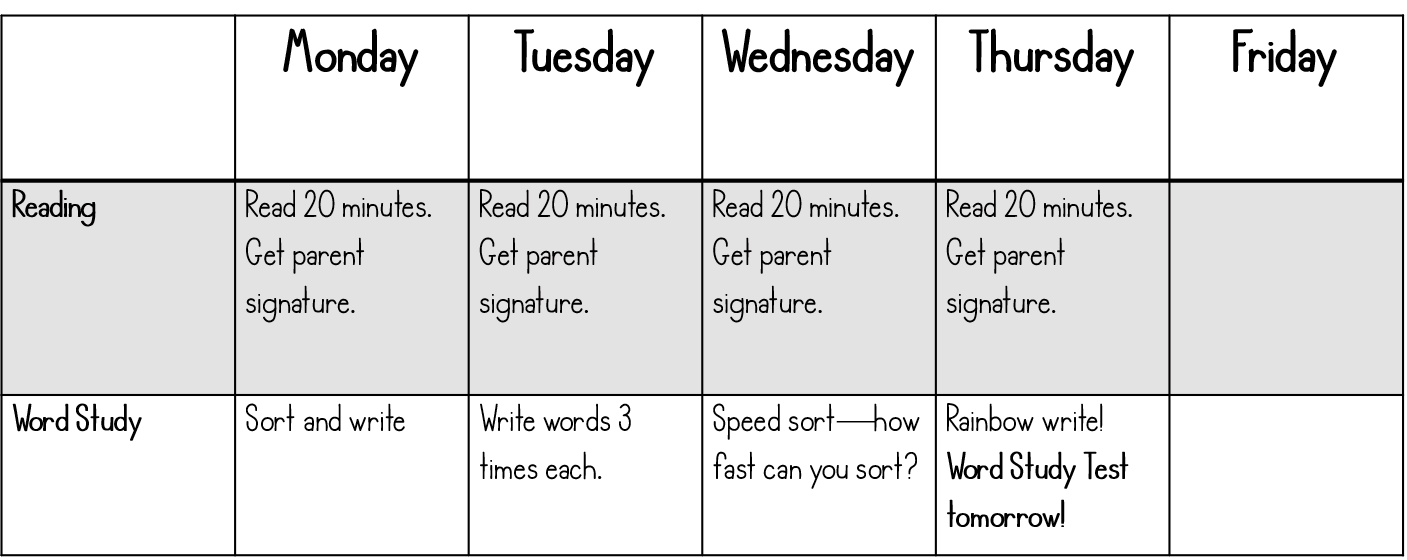

When I was a classroom teacher, this was how I taught word study. All students were given a DSA (a spelling inventory) in September. Based off their DSA, I would create groups. Each group would have their own spelling words for the week. On Monday I would introduce the word sorts in small group, and on Friday we would take the test. Friday small group was spent giving a word study test to each different group. Throughout the week, because time was so short, the only word work we did in my small group was to sort and read our words.

During independent work and homework throughout the week was where my students got their “real practice.” Students were asked to do things like rainbow write the words, roll and write their words, and to sort and write their words. Maybe once a week they would get with a partner and have a practice spelling test. I was doing all the things I was taught were best practice, and yet I still wasn’t getting results.

A few years ago, my district began mandating phonics skills in k-3. That meant there was a scope and sequence and required word lists. The first time I heard of it, I had to take several deep breaths. Because of the way I was trained, I was taught we had to teach children at their level. It took me a long time to become comfortable with the fact that having grade-level phonics expectations is okay. Not only that it is required by our state standards. This does not mean we are using the random spelling tests from when we were children. This means we are exposing all children to grade-level expectations, and systematically moving them through a sequence. Another huge change for my county was this-there wasn’t a county-provided word sort in sight.

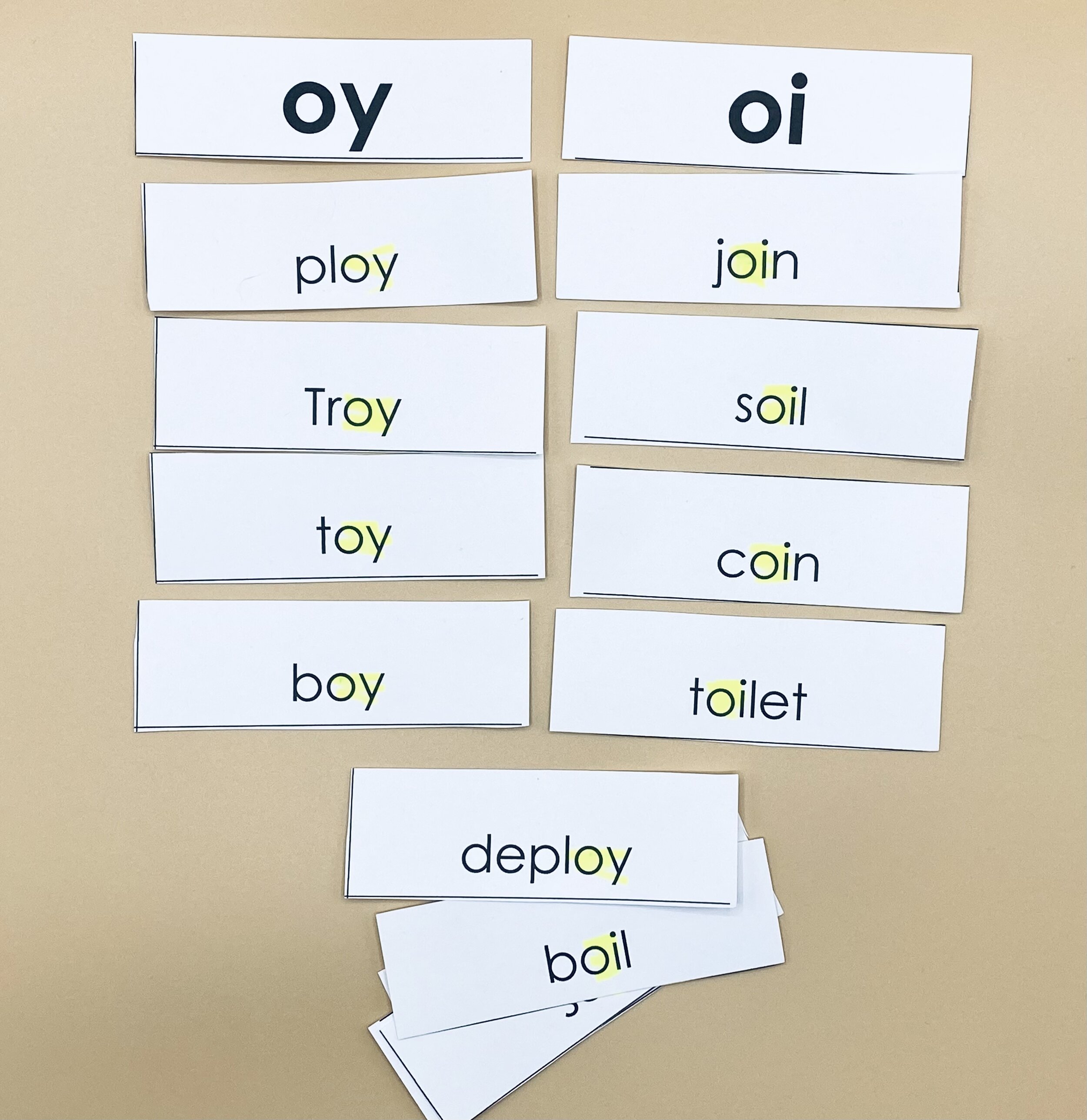

The biggest trouble with the “word sort” mentality is this—most of the activities associated with sorting words can be done without children ever actually knowing how to read or write a single word. Let’s use the oi and oy sort as an example. I could ask my children to sort these words. All they would need to do is find the oi and oy before they could effectively complete the activity. It simply becomes a matching game. Even if they can read the words, will it help them internalize the patterns? Without a discussion of which diphthongs we use in the middle, and which we use at the end, students will never remember the words past Friday’s spelling test.

Word sorts are not a systematic and explicit way to teach children. They are a single tool: one that, in all honesty, is very low on my list. I was taught that the sort WAS instruction, but it simply isn’t true. The act of sorting words by itself will never yield the results we desire. While the word sorts (at least the ones in Words Their Way) do move along a general continuum of skills, there’s no real explicit instruction. It’s more of a “sometimes words look like this, sometimes words look like this. Memorize which is which.” Introducing how to sort words is not the same thing as explicitly teaching a phonics skills.

Word sorts lend themselves to the “exploration” kind of teaching. Instead of teachers telling children the rule, children are often asked to come up with it themselves. There’s a long-standing notion in education that teachers aren’t supposed to directly teach concepts to children: instead, we are supposed to let children figure things out on their own. I want to tell every teacher this: it is okay to tell you children things. It is literally our job, and we need to stop feeling shame for explicit instruction.

Another reason against word sorts is that they are exhausting for teachers. I remember the pain of having to copy words for 5 different groups of kids each week. Then I would cut out an extra set of words for my small group table so they wouldn’t lose them. And CAN WE TALK ABOUT HOW LONG IT TOOK KIDS TO CUT OUT WORDS ON MONDAY?!?!?! Why waste so much time and effort on a single tool with limited benefits?

The biggest alternative to word sorts is this—explicit and systematic phonics instruction. That means this—we explicitly teach students the rule of English, and we do it using a scope and sequence. It is okay to teach a rule to your child. What does this mean? It means telling them that oi represents /oy/ in the middle, and that oy represents /oy/ at the end. Then, you practice. I use interactive notepages to introduce a rule to my students. Each child has a notebook for storing our rules.

I love this idea that I first heard from Decodable Readers Australia—rainbow sounds. We’ve all been there and had students practice rainbow writing words. In the old method, students use crayons or markers to make each letter in a word a different color. Instead of encouraging each letter to be a different color, with rainbow sounds, student will make each SOUND a different color. Think of the skill required for that kind of activity!

Instead of spending time sorting words, why don’t we spend time practicing words in context? We do this by using decodable texts. For decodable texts, I identify and read just the target skill (example: oi, oy) in the text, then read the text. Instead of sorting words, we can see what those words look like in context. We know the value of practice, and this is the kind of practice that will lead to results.

I’m embarrassed by the lack of dictation I had as a classroom teacher. I may have asked children to spell a few words, but I rarely asked them to write dictated sentences. Every single week, we students should spell, both in isolated words and in sentences, words that contain features they have learned. There should be a variety of old and new skills so that students retain previous learning.

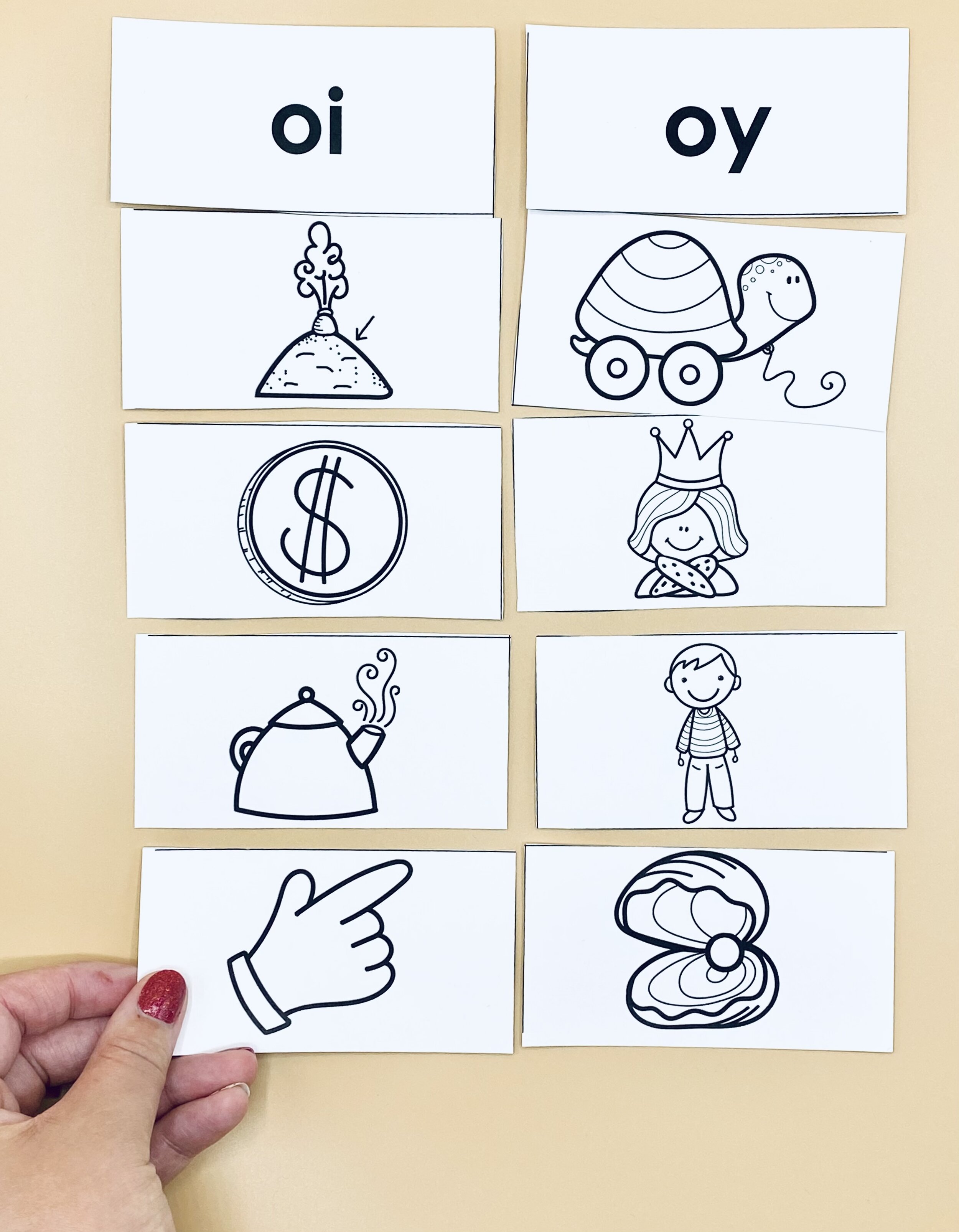

One sort that does require orthographic knowledge is this—a picture sort. Look at the oi/oy sort I’ve provided. How is this different from the sort above? There are no letters provided, and yet students have to know which grapheme is represented in order to effectively complete the sort. How do they do that? By thinking of the word and where the sound is made in each of those words. It looks like a simpler activity, the but the cognitive demand is actually much higher.

I know that some of you out there are going to say, “But I do teach explicitly and systematically with sorts.” If that’s the case, please carry on! In truth, however, most of us were taught that the sort was the instruction. The five strategies I presented you with today are not mind-blowing. They don’t take a lot of extra work and they seem simple. That’s the beauty in them. We need to let go of the idea that in order to be effective teachers, we have to create elaborate activities for our students. It’s not the amount of work we put into the activity that matters—it’s the amount of learning that occurs that counts.

Share This:

Savannah Campbell is a K-5 reading specialist. She has taught her entire 12-year teaching career at the school she went to as a child. She holds two master’s degrees in education from the College of William and Mary. Savannah is both Orton-Gillingham and LETRS trained. Her greatest hope in life is to allow all children to live the life they want by helping them to become literate individuals.

Savannah Campbell is a K-5 reading specialist. She has taught her entire 12-year teaching career at the school she went to as a child. She holds two master’s degrees in education from the College of William and Mary. Savannah is both Orton-Gillingham and LETRS trained. Her greatest hope in life is to allow all children to live the life they want by helping them to become literate individuals.

Feeling overwhelmed with all the terminology out there? Want to know the key terms all teachers need to teach phonics? In this FREE Rules of English cheat sheet, you get a 5 page pdf that takes you through the most important terms for understanding English—you’ll learn about digraphs, blends, syllable types, syllable divisions, and move. Grab today and take the stress out of your phonics prep!