Share This:

“Don’t throw the baby out with the bathwater.” This is the phrase I’ve heard most often when people want to defend balanced literacy. They’ll claim that there are still positive things about it and so we can’t overhaul the entire system. Or I will hear “All children learn to read differently and this is best for some children.” Or, my least favorite—“This is just another pendulum swing.” All of these sentiments are emotion-based, not fact-based. They’re meant to get a visceral reaction from us. But friends, nobody is throwing any babies. And balanced literacy must go.

In 2019, I interviewed for the reading specialist position I currently hold. In that interview, I clearly remember touting that we needed “balanced literacy” in our schools, and that children deserved to have access to texts that they could read (i.e. leveled texts). I spoke about how children needed practice in “reading, writing, listening, and speaking,” and my answer to how I would give them that was leveled texts.

I have two master’s degrees in education, and both of those degrees were steeped in balanced literacy. Since 2019, I’ve come to realize that my instruction actual harmed children. I had students in intervention who never got out of it. Balanced literacy is not a harmless practice—too many children get lost.

When I think back on the first 8 years of my teaching, I don’t think of the lessons or the instructional practices I used. Instead, I think of names and see their faces. I think of the child that used to cry every day during writing workshop and I thought they just needed “to find something they loved to write about.” I think of the child in first grade who I believed only needed more exposure to books they loved in order for them to learn to read. I believed learning to read required lots and lots of exposure to reading and writing, and that the teacher was the “guide on the side.”

Balanced literacy felt beautiful to me. It felt right. If I just gave them enough time to read and write, they would of course become readers and writers. It was about the volume of reading and writing time I was providing over everything else. Because reading came naturally to me, I assumed that’s how it would be for my all my learners.

But that’s not the case. Learning to read isn’t a natural process. We actually must rewire our brains to create the neural networks required for reading. For some, it does seem effortless. About 40% of our children will learn to read no matter what we do. But that leaves out too many kids. And I’m not here for 40% of students, I’m here for all of them. I’m not willing to leave anybody’s baby behind.

If you want to hear more about how reading really isn’t a natural process, check out Maryanne Wolf’s Proust and the Squid.* (Free on Kindle Unlimited!) Our brains are hard-wired to speak, but we are NOT wired to read.

So, what is missing from balanced literacy, then? In all the courses, books, and conferences I attended, this is the most egregious practice—not enough explicit instruction. If we are the “guide on the side,” we are putting the onus of teaching onto our students. I used to love having my students “discover” the concept I was trying to teach them. I thought a 5 minute mini-lesson was enough to get them going, followed by 45 minutes of independent reading.

The notion of balanced literacy typically involves a reader’s and writer’s workshop model. In the workshop method, students are given a short mini-lesson. After the mini-lesson, students are given extended periods of time to read or write. During that time, teachers may conference with students or pull small groups. But for as much time as possible, students are expected to independently read and write. That is a lot of unstructured time.

We know that explicit instruction is critical, and 5-15 minutes will not cut it. We need to move through a Gradual Release of Responsibility model, where we model (I do), then provide guided practice (We do), before we ask students to do things on their own (You do). Nothing I have seen in balanced literacy provides the appropriate type of scaffolding required with the Guided Release of Responsibility model. It all moves too fast into the “You do” component.

Don’t believe me? Pick up a reader’s workshop manual and see the verbiage they use for their mini-lesson. Does it provide enough support and practice to ensure all students are successful? Telling a student “Today and every day” is not the way you provide support.

The cueing strategies are persisting, although I’m grateful to see some of the narratives changing. The cueing strategies evolved from Ken Goodman’s theory about how children learn to read. He believed that instead of looking at every word while we read, we use meaning, structure, and syntax (MSV) to “guess” at what the word is. Goodman referred to reading as a “psycholinguistic guessing game.”

Now that we understand orthographic mapping and have science to back it up, we know this simply isn’t true. Simply put, orthographic mapping is when the oral language we know combines with the written form to create sight words. The written letter strings are both familiar and meaningful, and so we store them away until we need to read them, seemingly effortlessly. When we see a string of letters that have meaning to us, our brains automatically pull that word and its meaning out.

If that paragraph seemed complicated, its because it is. The best way to help most of our students achieve proficiency with reading is not to prompt them to use MSV. Instead, we prompt them by asking them to look at the letters and think of the sounds.

When I say that the cueing strategies are harmful, there’s actually research that has been done around this. Research was done at Stanford that showed that students who use the cueing strategies used the same part of their brain that poor users did.

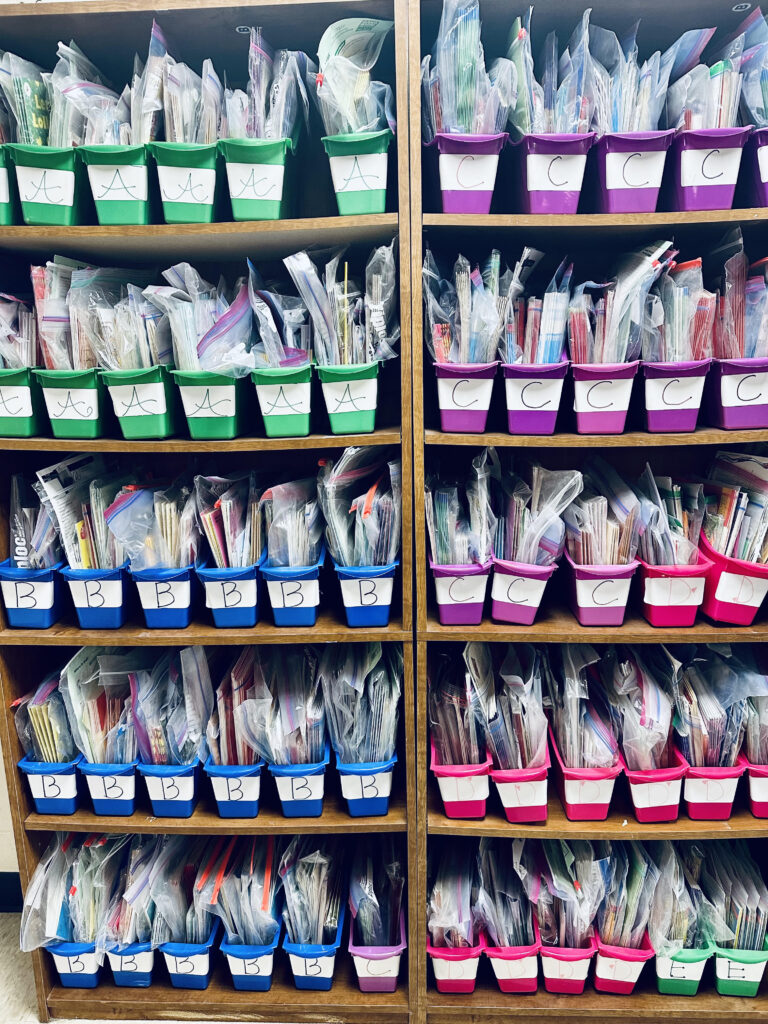

In addition to the cueing strategies, guided reading has persisted for decades. The defining feature of guided reading is leveled texts. In a guided reading lesson, the teacher works to move students up levels, much like leveling up in a video game. There are expected guided reading levels for each grade level, starting in kindergarten. In guided reading, the “level” reigns supreme (even if proponents claim it doesn’t).

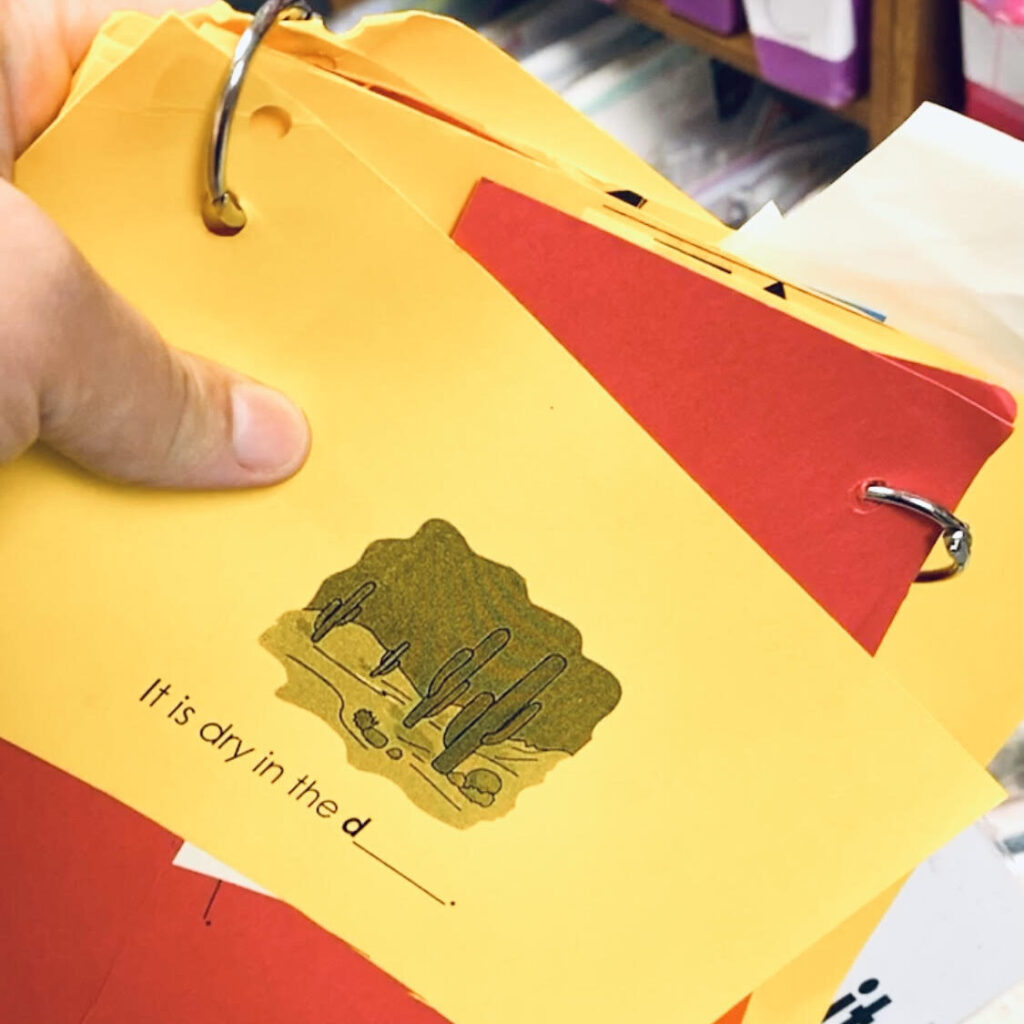

So, what’s wrong with leveled texts? In the early grades, the issue is that these texts are uncontrolled for phonics skills. Because there is no controlling for phonics skills, almost any early-leveled text will have a variety of phonics patterns unknown to the student. The student must then rely on the pattern of the text to memorize the structure, and most likely use a picture to figure out the rest. This is not reading, and this does not teach our students to read.

For our older students, guided reading levels can be a basic starting point, but we can never just assign a level to a student. Guided reading levels are not normed, and they are subjective depending on who is doing the leveling. Lastly, they can’t possibly take into account the background knowledge and vocabulary of a student. That’s a job only a teacher can do. So while you can use a guided reading level as a range for your students, we should not limit a child to a single guided reading level, because there is no controlling for content or patterns.

This is a loaded question, and it’s taken me years of unlearning and re-learning to find the answers. If you are reading this blog post and it feels like a personal attack, I get it. You’re allowed to be angry. You’re allowed to be annoyed with me. I felt the same way. But I ask you to listen with an open mind, and come back when you are ready. I say this as someone who has gone through every single one of those emotions.

What we do instead is this–we teach our children how to read, explicitly. We do not leave it up to chance. We teach phonics in the primary grades so our students know how to make sound-symbol correspondences. Then, we teach morphology and decoding of multisyllabic words as they get older so they can read whatever text you put in front of them.

And we teach comprehension from the start. Anyone who tells you that the Science of Reading is just about phonics doesn’t actually understand the Science of Reading. We explicitly teach children how to read, and we teach them to understand the texts in front of them (even if they can’t yet read it themselves).

Whenever I write something like this, there is inevitably the “I’ve used balanced literacy for years and it has worked for me and my students.” It’s hard to argue with anecdotal evidence. But I can’t help but think that in classrooms where balanced literacy has thrived, there are a couple of reasons why. First, it is important to remember that a sizeable number of students will be successful no matter the instructional method or program we use. Secondly, I have a sneaky suspicion that the successful balanced literacy teachers have more structured literacy in their days than they thought.

At the end of the day, we have to remember it isn’t about being right in this debate. It’s about getting it right for our students. We use the science to get it right. I get balanced literacy’s appeal-it felt right to me. But it didn’t move my students forward.

If you want anecdotal evidence, I have some for you. Since I started using a structured literacy approach, I’ve had more children than ever exit intervention and never come back. Some students I was able to reach for a year in the primary grades have gone on to be some of the most successful readers in their grades. Some students that I had for a couple years in intervention are now thriving on their own. I’ve seen the power of this work, and I’m so glad I embraced it, even when it was hard.

So for the sake of ALL our students, it is well past time for balanced literacy to make its exit.

*As an Amazon affiliate, I may earn a small commission for purchases made through my links (at no additional cost to you). Your support helps fuel my content creation. Thank you for shopping and discovering amazing new resources with me. Also, I would never share anything that I don’t believe in with every part of me!

Share This:

Savannah Campbell is a K-5 reading specialist. She has taught her entire 12-year teaching career at the school she went to as a child. She holds two master’s degrees in education from the College of William and Mary. Savannah is both Orton-Gillingham and LETRS trained. Her greatest hope in life is to allow all children to live the life they want by helping them to become literate individuals.

Savannah Campbell is a K-5 reading specialist. She has taught her entire 12-year teaching career at the school she went to as a child. She holds two master’s degrees in education from the College of William and Mary. Savannah is both Orton-Gillingham and LETRS trained. Her greatest hope in life is to allow all children to live the life they want by helping them to become literate individuals.

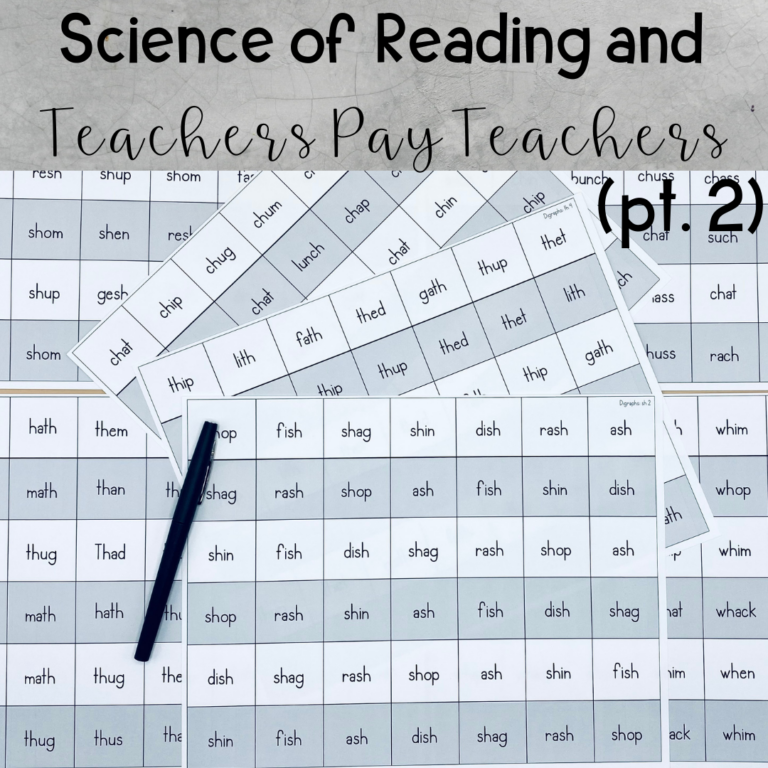

Feeling overwhelmed with all the terminology out there? Want to know the key terms all teachers need to teach phonics? In this FREE Rules of English cheat sheet, you get a 5 page pdf that takes you through the most important terms for understanding English—you’ll learn about digraphs, blends, syllable types, syllable divisions, and move. Grab today and take the stress out of your phonics prep!