Share This:

When I first started writing this blog post, I said to myself “This is boring. Literally nobody is going to read this blog post.” So I need to be honest with you—text structures are not the most exciting topic I’m ever going to share with you. But text structures are an important way we can help students comprehend a text. And I want you to know that this blog post will be living in the universe whenever you need it. So maybe today isn’t the day you read it through, but when you’re ready to start delving into the different text structures to help improve comprehension, revisit this page for clarity and inspiration while teaching them.

According to Nancy Hennessy*, “intervention studies have shown that children can benefit from explicit instruction in all structures as early as second grade with appropriate differentiation”(Hennessy, 2021, p.133). Meaning, teaching text structures is a concrete way to help improve our children’s reading comprehension.

Furthermore, I love what the LETRS manual says about text structure. They say that “An existing schema for the structure of… any form of text provides a mental framework that guides the search for meaning. It provides a mental model into which new, incoming information can be filled”(Paulson & Moats, 2010, p.132). When we teach text structures, we are helping our students to build background knowledge. If you know what kind of information to expect in a text, the mental load is lessened. Anytime I can take some of the burden off of my students to help them better access the text, I’m there!

As I’m discussing these text structures, I’m discussing them for nonfiction texts. Why? Well, fiction tends to have a pretty familiar structure. We have characters who face a problem, who must then try to solve that problem. Obstacles will come along the way, making it difficult to solve the problem. At the end, some kind of a resolution is reached.

Fiction stories may differ in content and there are some variations to this pattern, but that is the typical setup for a fiction story.

Nonfiction, however, is very different. Nonfiction presents itself in many different text structures. It matters because the setup of the text, and the kind of understandings the author wants to leave you with, can be very different depending on the text structure you are looking at. For example, a problem and solution text structure may have more opinions in it than a descriptive text.

Nonfiction can also be a lot harder for many of our students. Nonfiction texts may contain specialized language, have denser sentence structures, and are teaching unfamiliar concepts and topics.

So, let’s explore each of the different nonfiction text structures. Then, let’s talk about how we can incorporate them into our current teachings.

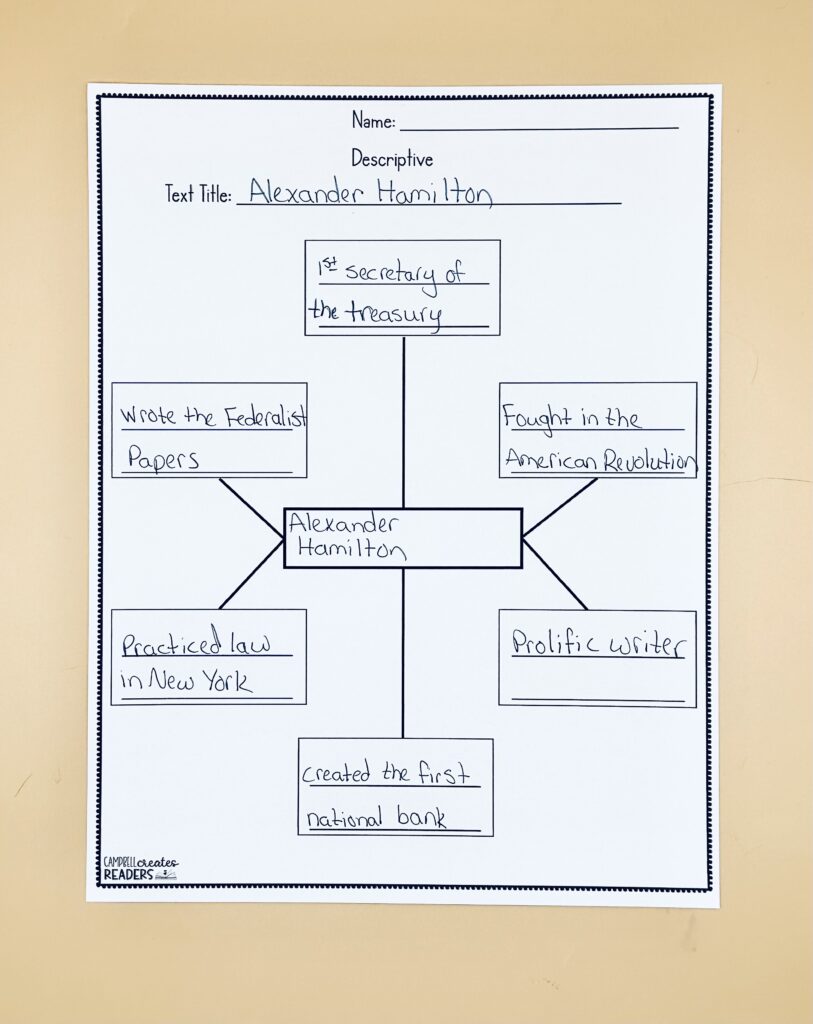

I find descriptive texts to be the easiest to teach. These informational texts give descriptions of people, places, things, events, or general knowledge. The goal is to give the attributes of the topic, in no particular order.

If you read a book about foxes, for example, it will most likely be a descriptive text that gives you all kinds of information about the animal. You wouldn’t need to necessarily read the chapter on habitat before you read the chapter on physical characteristics.

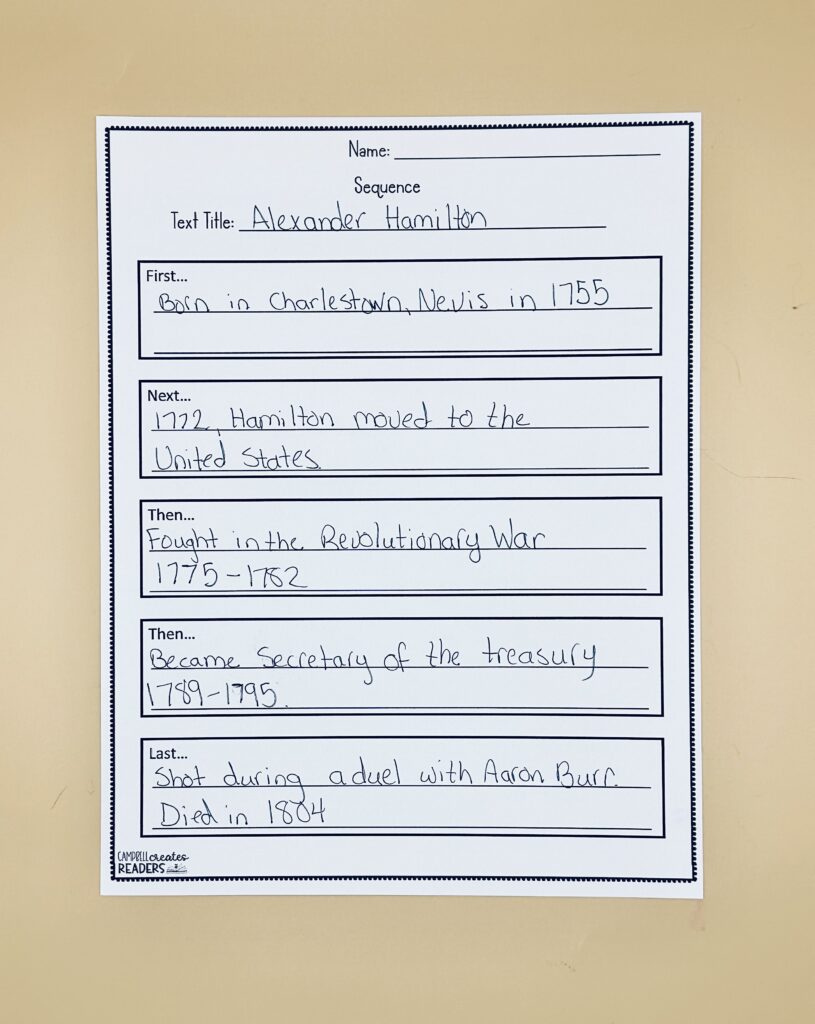

A sequence text will explain something in a sequential order. This can be both a time order (the events of the American Revolution) or sequential order (how to make a pb&j).

Unlike many of the other informational text structures, these texts make the most sense when they are read in order of how it is presented.

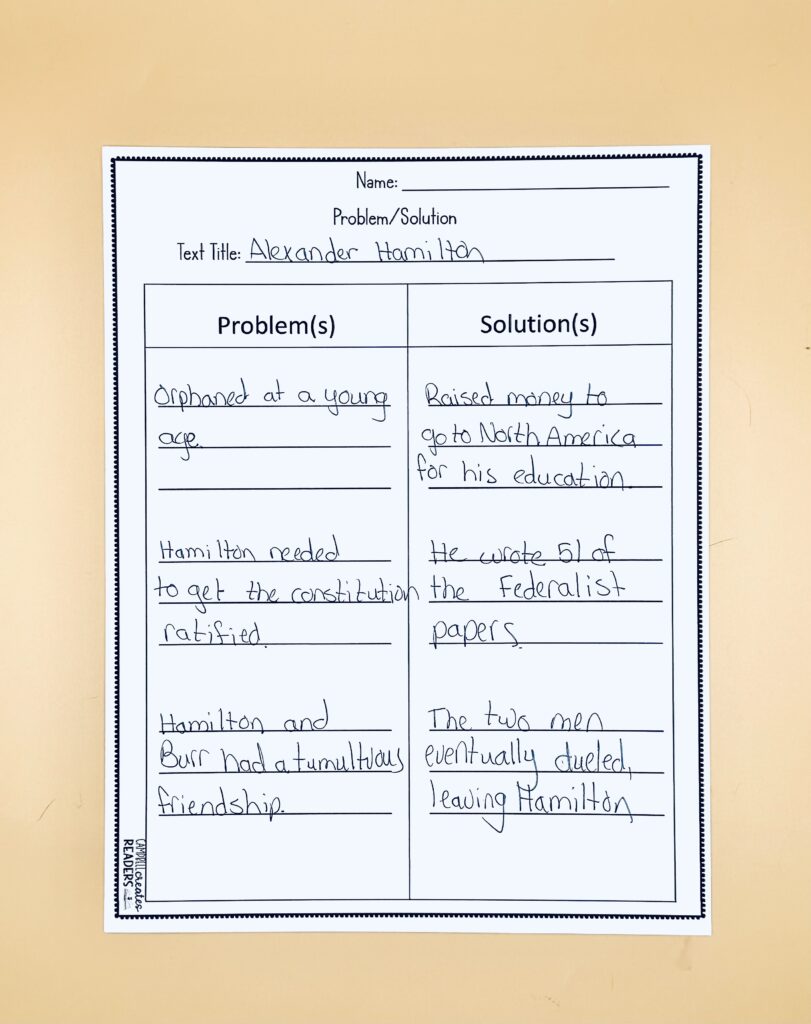

The overarching theme of a problem and solution text is to introduce a problem and give the steps taken to either solve the problem or come to a resolution. There may be multiple problems, but often one overarching problem.

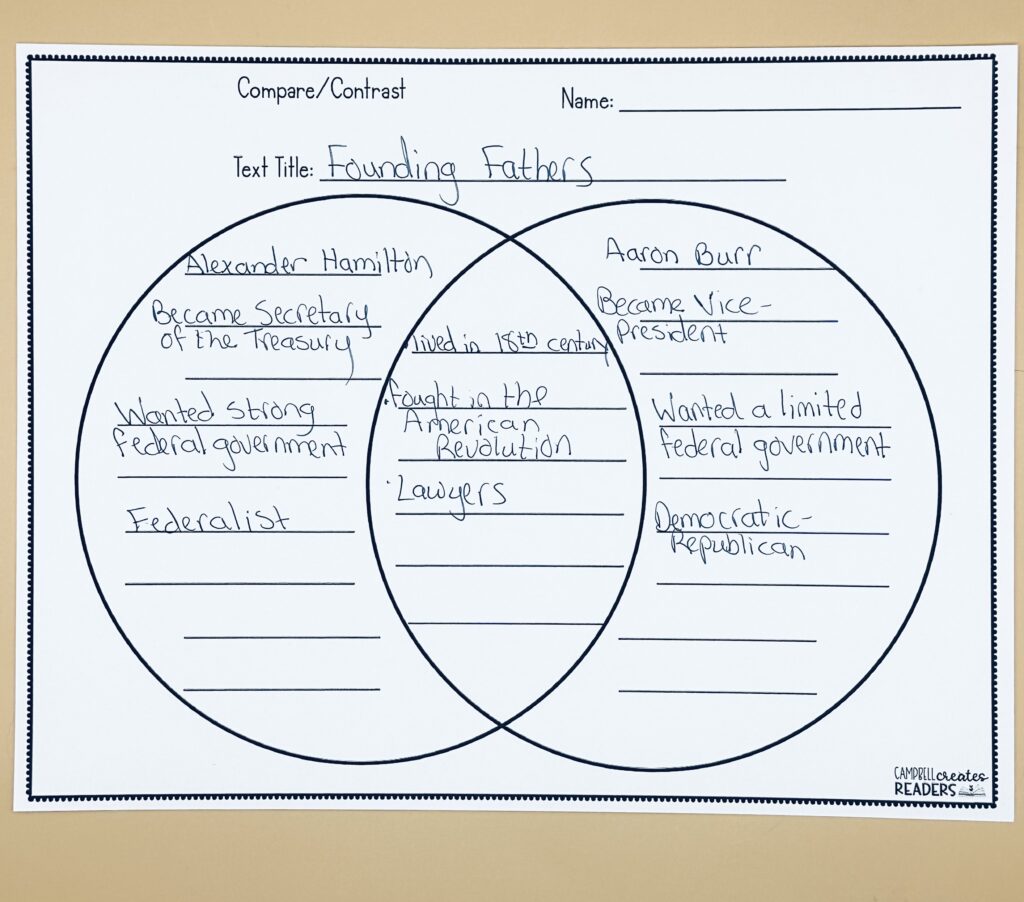

In this kind of text, the author is describing two or more things. The author is detailing how they are both alike (comparing), as well as how they differ (contrasting). If you are looking to teach this text structure, but can’t find a single text that does this well, it is acceptable to find two texts and compare them.

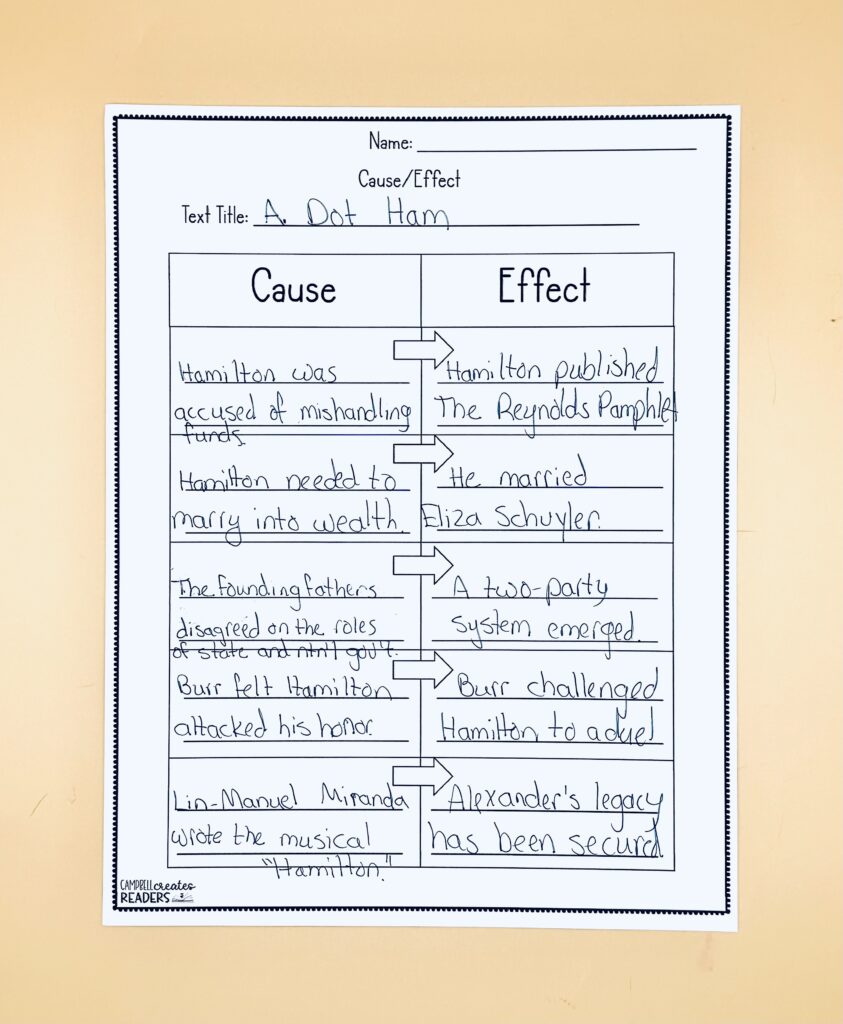

Cause and effect texts explains why something has happened, and then gives you the result of that event or action. An often overlooked component of cause and effect texts is simply stopping when students can identify one cause and one effect.

The reality is that there are often multiple causes that lead to something happening. Likewise, a single cause can have multiple effects. To really make this tricky, an effect can become a cause. For example, a tornado can cause damage to a hospital. Then, because there is damage to a hospital, the patients must be taken to another place. The world doesn’t end with one cause and effect, and these continuous cycling of cause and effect can be troubling for our students.

Sometimes, I get paralyzed with panic over starting something that I just never take that first step. Especially when a topic seems very heavy or involved, the first actions you take may seem overwhelming. So, I want to share a few tips for getting started with teaching text structures that won’t make you call it quits before you even begin.

I used to think about texts within two realms—fiction or nonfiction. In fact, I made that dichotomy earlier in this blog post. However, I think as educators we need to begin making the shift away from fiction and nonfiction as the two big distinctions. Instead, it is really about narrative vs. informational texts.

The reason this is important is because sometimes we will have nonfiction texts that read like a story. A great example of this is a biography. Oftentimes biographies will be narrative in form, complete with quotations and specific actions from that person’s life. So while the bulk of the story is completely true, the author has to take some liberties with things like dialogue, because we don’t actually know what those individuals said.

So, if you have a book that reads like a narrative, but is nonfiction, we call that narrative nonfiction. The structure of the story is the same as a fiction narrative, so we would lump it in with those. All the text structures we explored today would fall under the informational category.

I never thought much about text structures, to be honest. I didn’t see their value, didn’t see how they could help become an anchor for our children’s learning. But now, I get it. When I think of text structures as a kind of background knowledge, it illuminates the importance. Our students come to us with a varying levels of background knowledge, making it feel like an uphill battle. This is one way we can level the playing field.

Hennessy, Nancy Lewis. The Reading Comprehension Blueprint: Helping Students Make Meaning from Text. Paul H. Brookes Publishing, 2021.

Paulson L. H. & Moats L. C. (2010). Letrs for early childhood educators. Cambium Learning ; Sopris West.

*As an Amazon affiliate, I may receive a small commission on items purchased through my link. This is at no cost to you, and helps me to continue to provide weekly free content!

Share This:

Savannah Campbell is a K-5 reading specialist. She has taught her entire 12-year teaching career at the school she went to as a child. She holds two master’s degrees in education from the College of William and Mary. Savannah is both Orton-Gillingham and LETRS trained. Her greatest hope in life is to allow all children to live the life they want by helping them to become literate individuals.

Savannah Campbell is a K-5 reading specialist. She has taught her entire 12-year teaching career at the school she went to as a child. She holds two master’s degrees in education from the College of William and Mary. Savannah is both Orton-Gillingham and LETRS trained. Her greatest hope in life is to allow all children to live the life they want by helping them to become literate individuals.

Feeling overwhelmed with all the terminology out there? Want to know the key terms all teachers need to teach phonics? In this FREE Rules of English cheat sheet, you get a 5 page pdf that takes you through the most important terms for understanding English—you’ll learn about digraphs, blends, syllable types, syllable divisions, and move. Grab today and take the stress out of your phonics prep!