Share This:

There has been a lot of talk in the Science of Reading community about foundational skills for our beginning readers, and rightfully so. Before 2019, I didn’t have the faintest idea how to actually teach phonics.

But once I had the foundational skills in order, I realized that my instruction for the upper grades was lacking as well.

When decoding is not an issue, it is background knowledge and vocabulary that are the biggest indicators of how well a child will understand a text (Wexler, 2019). Armed with this knowledge, I’ve made it my goal to expand both of those things for my upper-grade students. I will continue honing and fine-tuning my understandings, but I have seen great growth from using the ideas outlined below in my small group instruction.

When my students no longer need single-syllable decoding help, I follow a pretty typical structure in my lessons. It includes:

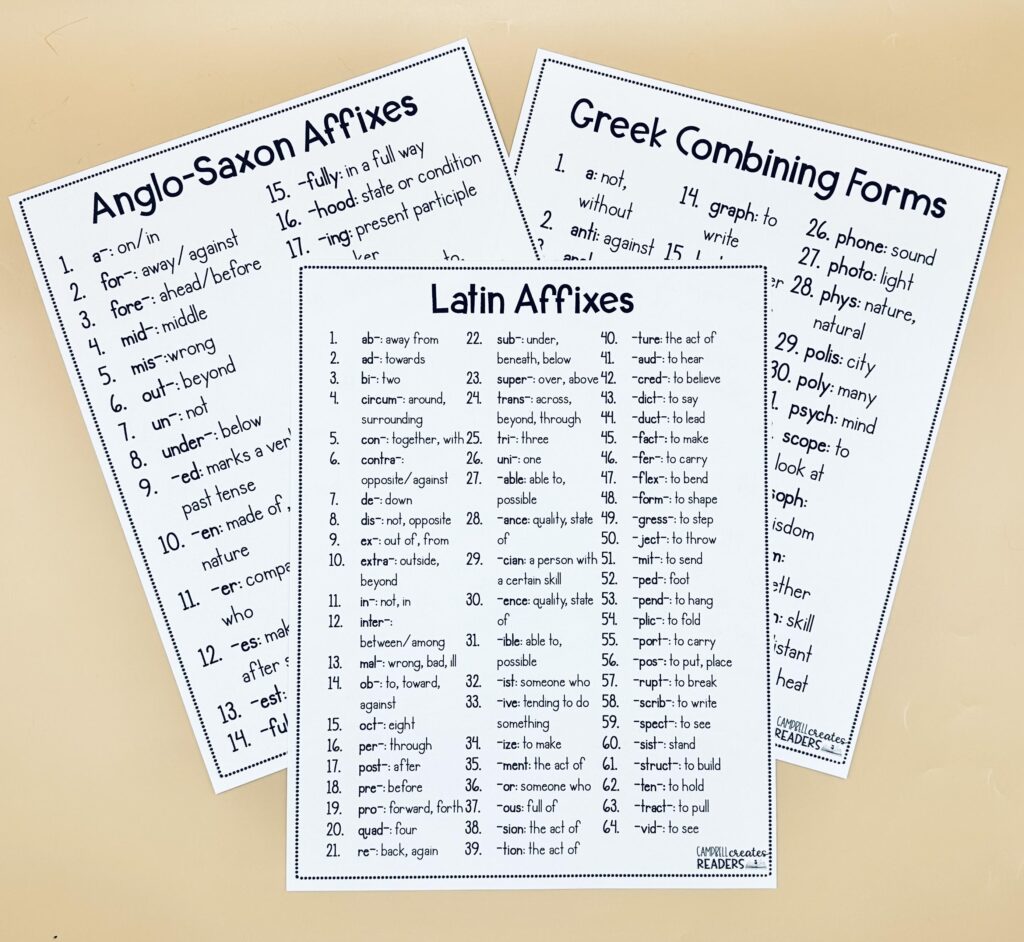

I’ve talked a lot about morphology over the past year because it’s just not a conversation we are having enough. With upper elementary students, instead of starting with basic sound-symbol correspondences (think ai represents /a/, igh represent /i/ before a t), I am explicitly teaching them morphemes. I start with Anglo-Saxon, but quickly begin to interweave Latin into our lessons. Unsure about what all the affixes mean? Don’t worry, I’ve got a master list of definitions you can download for free!

I follow a structure to teaching morphemes that is pretty similar to how I teach phoneme-grapheme correspondences. I will explicitly teach the morpheme and its definition, give guided practice with the morpheme, and then allow students time to practice it. (I do, we do, you do. Sound familiar?)

Here is an example of how I would introduce a morpheme, the “I do” part of the lesson. I’m sharing a sample script to remind you that it doesn’t have to be difficult or fancy.

Today, we are learning the prefix “con. Con is a prefix that means together or with. Say ‘con.’”

Students repeat, teacher writes the prefix and definition on the board.

Listen and watch as I read some words with the prefix and discuss the meaning.

Teacher writes conduct, construction, congress on the board.

Conduct literally means to lead together. This makes sense to me, because a conductor is someone who leads an orchestra to come together and make great music.

Construction literally means the act of building together. Well construction workers are definitely building-that’s their job!

Congress literally means to walk together. Congress is a part of our government that should “walk together” for the good of the people.

It is that simple, and that explicit. After I introduce the morpheme, we go straight into our morphology notepages, followed by morphology fluency grids. You could also ask children to spell words with the target morpheme. I usually wait until the following day because many of my interactive notepages already ask students to write morphemes.

A gamechanger for me has been incorporating daily review. It is not enough to teach a morpheme for a week, take a test, and then move onto the next one. It is only when we show students how the current affixes fit in with all the previous ones we’ve done that we have the greatest impact.

I review morphemes in a few ways: sound decks, dictation practice, and review decks. If you want to learn more, I have a free webinar on cumulative review in grades 3-5 that can help you get started!

After my morphology lesson, my reading lesson looks similar to how it looked before I switched to a structured literacy approach. When I was fully immersed in guided reading, I would choose a book based on a level, target a skill, and then we would read and do comprehension work.

There are some key shifts now, though. I may look at a guided reading level as a guide, but I am not tying myself to a single level for my students. Instead, I am thinking about their interests, their background knowledge, and how I can build their understanding of texts and the world.

You can use Lexile levels, guided reading levels, or DRA levels, but just remember that it isn’t actually about the level. You shouldn’t have a kid who can only read level R books, or a group that is just reading level M. Small group instruction isn’t about moving students through levels. Instead, think of a level as a starting point for looking at texts. Then, use what you know about your students’ background knowledge and vocabulary to decide which text to use.

When I was teaching guided reading, most of my instruction revolved around “strategy” work. For example, I’d think, “this week we are teaching context clues, so we’re going to be looking for context clues in our texts.”

While the National Reading Panel (2000) did identify strategy instruction as a beneficial practice, I think people would be surprised to learn that the strategies aren’t exactly what most of us think. The following are the comprehension strategies listed by the National Reading Panel as supported by research:

So you see, it’s not about whether or not children can make text-to-self connections or if they can simply make a prediction. It’s not about isolated strategy work, but about how we teach children to flexibly use strategies while reading to understand the text.

I am always asking myself, “What background knowledge and vocabulary will my students need to understand this text?” Instead of focusing on a skill and finding a text to match that skill, I will find the text I want to use first. Then, I ask which skills they need to understand that specific text. Can I use a graphic organizer to support that learning? Can we write a summary together to support our understandings? When it comes to comprehension, the text helps point me in the direction I need to go.

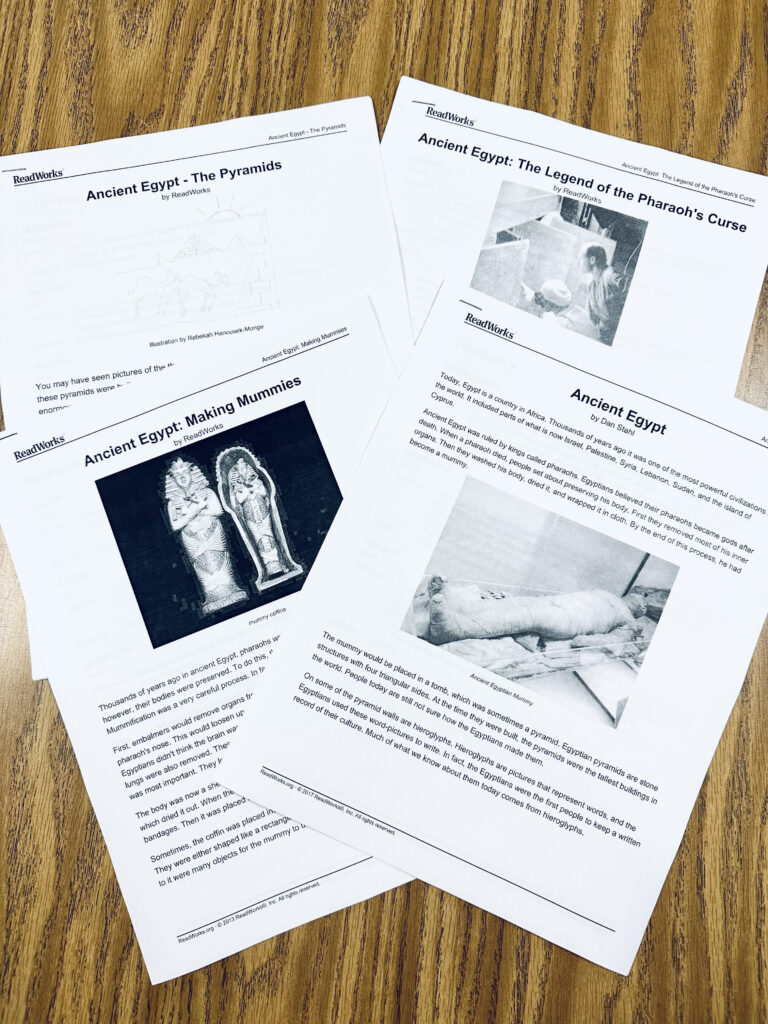

Now that I’m not moving students through “levels,” I like to think about moving students through topics and themes. For nonfiction, I will use science and social studies standards to build background knowledge and vocabulary around a topic, either before or during a unit. If I know my students will soon learn about magnetism in science class, I will pull 2-3 texts on the topic. This way, when they are exposed to the content in class, they already have some basic understandings about it.

Remember, knowledge is like Velcro. The more knowledge we give them ahead of time, the easier new knowledge will be to stick to it. I will never forget when our 5th grade science teacher came to me and told me that one of my kids was the only child who could answer her question during an electricity unit. That’s the power of this work.

My favorite place for finding FREE science and social studies texts is ReadWorks. ALL of their texts are free for teachers.

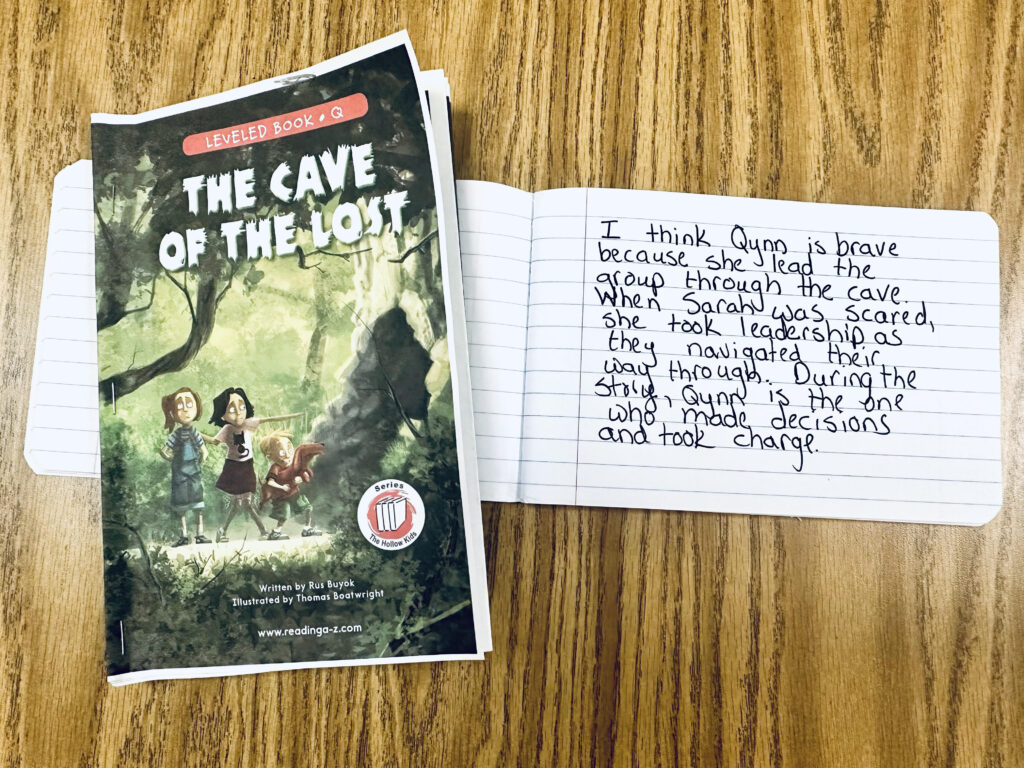

When reading fiction, try looking for themes. Could you pull several books that focus on perseverance, acceptance, difficult choices? Series are also great because students can get a deeper understanding of characters across several texts. I like using the ones from Raz-Kids because they are short (we typically read them in 2 days) and the students can take the printed copy home with them afterwards.

You can use a novel, but novels can take months to get through. For me, they aren’t worth it in small group. I need shorter texts so we can get through a greater volume.

Without a doubt, one of the key things to include in your lesson is writing. Writing and reading are so intertwined, and we can help our students better understand what they’ve read by asking them to write.

Every time we finish reading a text, I ask my students to write for me. In a nonfiction text, it might be something like “How did the relationship between the settlers and the Native Americans change. Use evidence from texts you’ve read.” In a fiction text, I might ask “Is Qynn brave? Use evidence from the text to support your answer.” I ask questions that can only be answered if they have an understanding of the concept and texts.

Graphic organizers are another way to get students writing about their reading. When we use graphic organizers, we are helping frame their thinking about how texts work. A graphic organizer could also be a “pre-planning” sheet to help them write a paragraph or essay about the topic.

The biggest misconception I see about vocabulary instruction is this: many people see vocabulary instruction as something IN ADDITION to your comprehension instruction. I view vocabulary instruction as a critical component of the comprehension work I am already doing.

The vocabulary work that you do shouldn’t come from a random list, but from the texts that you are already using. When choosing words to teach, you want to think about which words will serve students the best across multiple texts and multiple disciplines. Isotope is a great word, but will it be one my students need to learn about across multiple contexts? Always try to use words that will come up again and again.

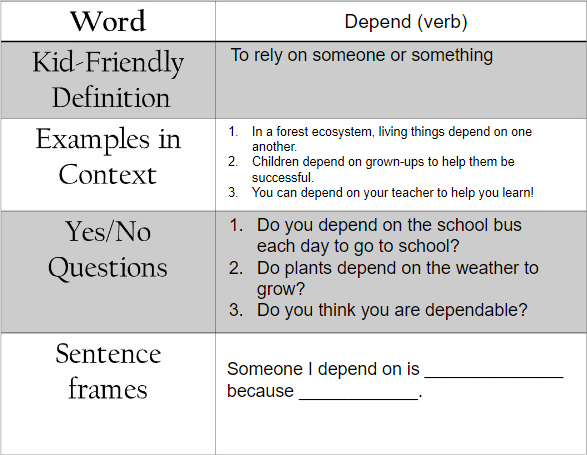

I like introducing a word using the simple planning framework below. I give students a student-friendly definition, share some examples in context, ask yes or no questions, and ask them to fill in a sentence stem.

There’s so many different ways we can practice vocabulary–but that’s a post for another day! My all-time favorite resource for understanding vocabulary is Bringing Words to Life* by Beck and McKeown. It’s been a game-changer in how I understand and teach vocabulary to my students.

If you have a student who is in fourth or fifth grade and STILL cannot decode, what do you do? My answer is my own opinion, but it is one based off of what I have seen over the past several years. If a child is in 4th or 5th grade and they still cannot decode, that means that what we have done for them for the past 5-6 years has not worked.

This year with my fifth graders, I decided I wasn’t starting from scratch again. I simply cannot spend 9 weeks with fifth graders teaching them all the vowel teams. Instead, I started by teaching the six syllable types, but ONLY in multisyllabic words. I am building the word recognition strand of the reading rope, but in a way that is going to (hopefully) help them the most.

I found that it wasn’t that my fifth graders cannot decode single-syllable words, its that they don’t know how syllables work and what to do when they come across multisyllabic words, which is what most of their work is. So ask yourself—do they really not know how to read chain and mark? Or is that they haven’t had enough practice with them within multisyllabic words and inside texts?

After teaching them about the six syllable types within multisyllabic words, I began teaching affixes like I mentioned above.

I wish comprehension were as straightforward as phonics. With phonics, it may not be easy work, but it is predictable work. Comprehension instruction is just a lot messier. I am always trying to keep in mind that I am building their understandings of words and the world. If we can help them understand key concepts about our world, AND give them the vocabulary for it, then our comprehension instruction will be powerful.

I know that my small group instruction will grow, evolve, change. But right now, this work that I am doing is producing results for my students. And that motivates me to keep doing it.

*As an Amazon affiliate, I may earn a small commission for purchases made through my links (at no additional cost to you). Your support helps fuel my content creation. Thank you for shopping and discovering amazing new resources with me. Also, I would never share anything that I don’t believe in with every part of me!

Share This:

Savannah Campbell is a K-5 reading specialist. She has taught her entire 12-year teaching career at the school she went to as a child. She holds two master’s degrees in education from the College of William and Mary. Savannah is both Orton-Gillingham and LETRS trained. Her greatest hope in life is to allow all children to live the life they want by helping them to become literate individuals.

Savannah Campbell is a K-5 reading specialist. She has taught her entire 12-year teaching career at the school she went to as a child. She holds two master’s degrees in education from the College of William and Mary. Savannah is both Orton-Gillingham and LETRS trained. Her greatest hope in life is to allow all children to live the life they want by helping them to become literate individuals.

Feeling overwhelmed with all the terminology out there? Want to know the key terms all teachers need to teach phonics? In this FREE Rules of English cheat sheet, you get a 5 page pdf that takes you through the most important terms for understanding English—you’ll learn about digraphs, blends, syllable types, syllable divisions, and move. Grab today and take the stress out of your phonics prep!