Share This:

As the importance of phonics has come to light, a resurgence of explicit phonics instruction has made its way into classrooms across the country. From kindergarten through fifth grade and beyond, phonics is being taught. But, is phonics for older students necessary?

Because some of these practices are helping our younger students, it makes sense that we would want to try it with our older children too. For the most part, however, students above 3rd grade do not need instruction in single-syllable words or phonemic awareness instruction. (3rd graders are in that transition year where they’re still being taught some of the more complex patterns of single-syllable words.) Yet I’m still seeing things like phonemic awareness curriculums in upper-elementary and magic e being taught to typically developing 4th graders.

We have spent so much time getting it right for the littles, it’s high time more people talk about how we can strengthen word recognition for our older students.

The National Reading Panel shone very favorable light on phonics instruction, especially for our younger students. Without a doubt, the sweet spot for teaching phonics is in kindergarten and first grade. Where the overall effect size for teaching phonics is .41 (a moderate effect), the effect size for kindergarten students at risk was .58, at-risk first graders was .74, and typically developing first graders was .48. This shows that phonics has a moderate effect size in kindergarten and first grade, with an even higher effect size for students who are at risk.

For 2-6th grade typically achieving readers, the effect size was .27. For 2-6th grade students who were low achieving, the effect size was only .15. Those effect sizes are considered low and insignificant, respectively.

The National Reading Panel explains the potential reasons for the low effect sizes when it comes to phonics for older students. They state, “Possible reasons might be that the phonics instruction provided to low-achieving readers was not sufficiently intense, that their reading difficulties arose from sources not treated by phonics instruction such as poor comprehension, or that there were too few cases… to yield reliable findings”(NRP, 2000, 2-133). Emphasis added by me, because we’re going to get into intensity of instruction later.

This can feel discouraging. I remember when I was in teacher prep program I heard that if a child wasn’t reading on grade level by the end of 3rd grade, they never would. I thought to myself (as an aspiring 4th grade teacher) “What’s the point, then?”

But I want to remind you that difficult does not mean impossible. And the only other option is to give up. So yes, it may be more difficult, but we still have a chance to get it right for the sake of these kids. Phonics for older students may not be required for all, but we cannot give up on those students who need it.

One mistake I see for older struggling readers is that they are not receiving access to the core curriculum. Because they are behind, they may have watered-down words lists or watered-down curriculum. While the intention is good, it means that they are missing out on key parts of the curriculum, year after year.

I know that not everyone agrees with me on the fact that all children need to receive core instruction. But for my district, this is a key component of our MTSS model. All children receive access to solid core instruction, and then we differentiate to meet their needs.

What happens when children don’t receive access to the core? They fall further and further behind. There is no reason why children cannot be exposed to grade-level skills. For example, even if a child is working on magic e, they can still see vowel teams. If a child is working on vowel teams, they can absolutely be exposed to morphology. A student whose decoding is low should not be excluded from comprehension instruction just because they can’t read the words themselves.

I’ve found that when children are exposed to the material, it makes it so much easier for them to master it once we get there in intervention. Without that exposure, it’s like starting from scratch. We simply have an obligation to give all children exposure to core.

When I have older struggling readers, they have been taught for years and still cannot decode efficiently. If they have been in my school since the start, I know they have received phonics instruction, so what do I do? Spend more time doing the same thing?

I have found that with older students, it is not whether or not they can read “cat” or “bird.” Instead, it is that they cannot decode words of two syllables and beyond. Furthermore, they don’t have word attack strategies like flexing their vowel sounds. So, I focus my attention on two things: ensuring they have enough practice to reach automaticity and giving them instruction in how to decode larger words.

We (as a collective) do a really good job of explicitly teaching single-syllable phonics instruction to students. No, really, we deserve a pat on the back. If someone did a study on the number of quality decodables available today versus ten years ago, I think we’d be stunned.

But there seems to be this middle ground between decodables and authentic text that we aren’t addressing. We cannot just teach students single-syllable words, and then expect them to read authentic texts. I’m noticing a strong need for instruction that helps to bridge that gap.

There are three things we can teach as educators to help bridge the gap–syllable types, decoding multisyllabic words, and morphology. But above all else, we must give them the enough practice so that they can master the skills!

We cannot overestimate the importance of practice. Many children will orthographically map words with between 1-4 exposures. But for our struggling readers, it can take dozens and dozens of exposures before they can automatically and effortlessly recall a specific word. Remember the National Reading Panel’s potential reasons why phonics instruction had such a low effect size for older readers? They stated it could be that they didn’t have intense enough instruction. For me, intensity refers to the pace and the amount of practice these children need.

So I explicitly teach them the skills they are lacking, and I give them the practice they need to become automatic. Whenever someone asks me what they should do with a child who struggles, my first question is always “How much practice do they have on new and previous skills?” If the answer isn’t daily, that is my first recommendation.

One decodable a week just won’t cut it. They need opportunities throughout the week to read and spell new skills and to review previous skills.

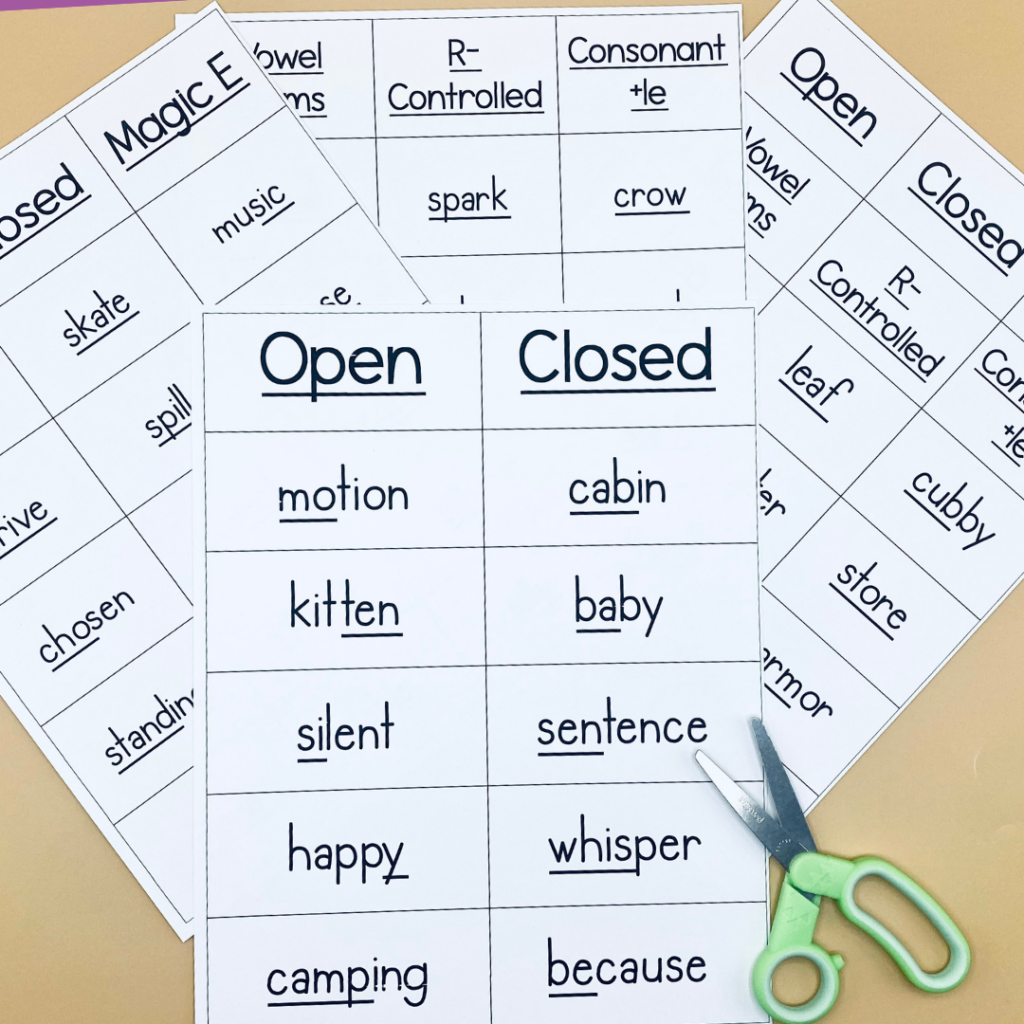

Did you know that all English words are made up of one or more of six syllable types? Think about that. There are just 6 different kinds of syllables. If we can teach our students to read those 6 kinds of syllables, we can teach them to read anything.

With students starting in 3rd grade and up, I do a 6 syllable types units. But here’s the thing—I teach them the 6 syllable types mostly within multisyllabic words. So we are not just reading go, hi, bat, and kick. We are reading multisyllabic words like fantastic, mobile, silent, and more.

The 6 syllable types are as follows: open, closed, magic e, r-controlled, vowel team, and consonant + le.

Open Syllables: When a syllable ends in a single vowel, it is an open syllable. The vowel sound is long. (Ex: go, hi, robot, open)

Closed Syllables: When you have only one vowel, followed by one or more consonants in a syllable, it is a closed syllable. The vowel sound is short. (Ex: ask, stick, itch, it,)

Magic-e (Also called silent-e): When you add a silent e to the end of a closed syllable, it makes the vowel sound a long sound. (Ex: make, Pete, trike, stove)

R-controlled (Also called vowel-r syllable): When a vowel is followed by the letter r, it is an r-controlled syllable. The r distorts the sound of the vowel. (Ex: starve, hurt, bird, thorn)

Vowel-Team: When two vowels come together to represents one sound, it is a vowel team. (Ex: chain, key, boat, green.) Some will have diphthongs as a 7th syllable type, but I include them here.

Consonant + le: This is the only syllable type that must come in a multisyllabic word. Consonant + le is also called a final stable syllable–meaning all three letters must stay together and represent a single syllable. (Ex: table, puzzle, whistle)

In math, we always use manipulatives. But reading doesn’t get nearly as many. Anytime we can make this difficult process of learning to read more concrete, the better. A great place to do this with our older struggling readers is by explicitly teaching them how to decode multisyllabic words.

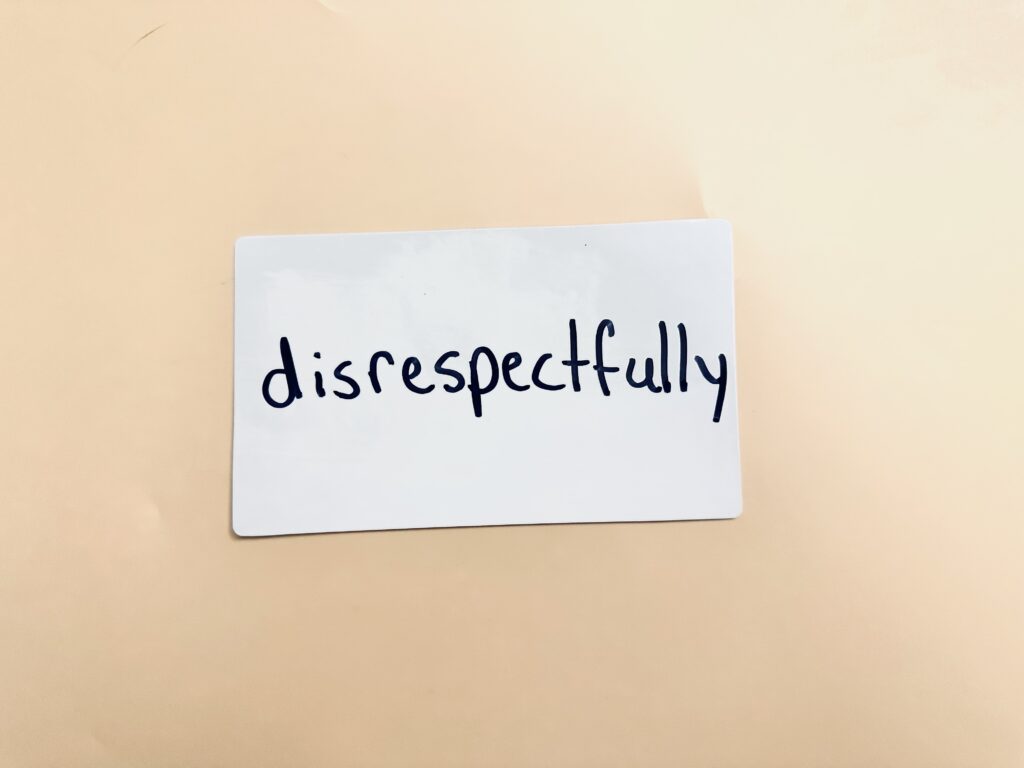

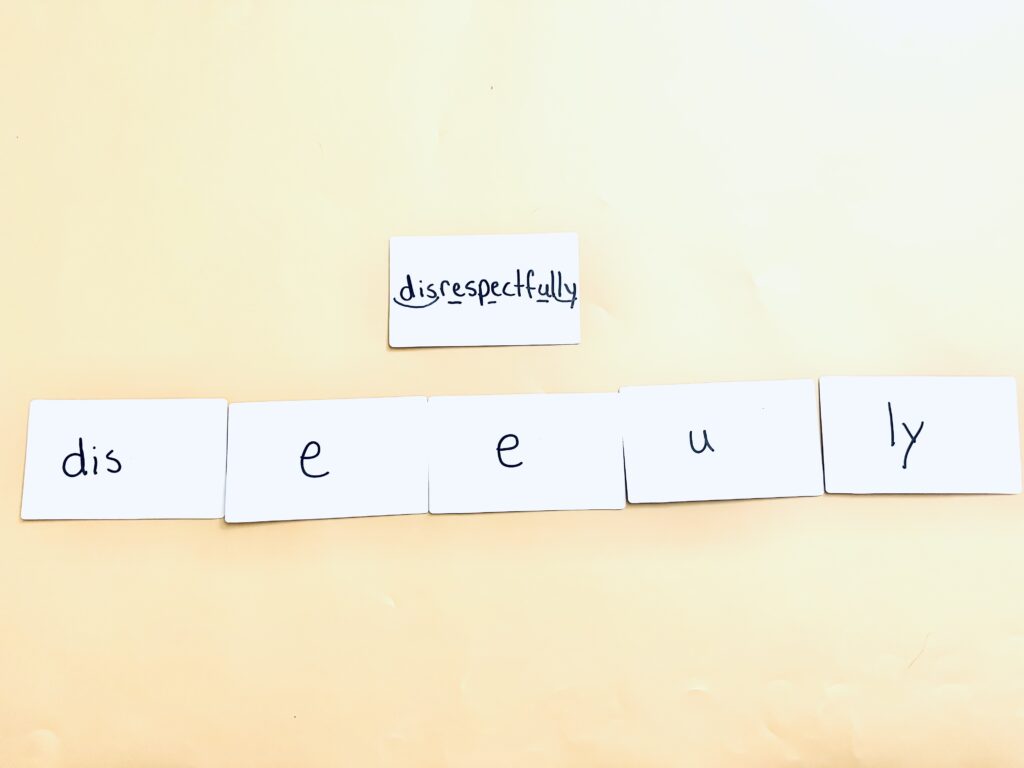

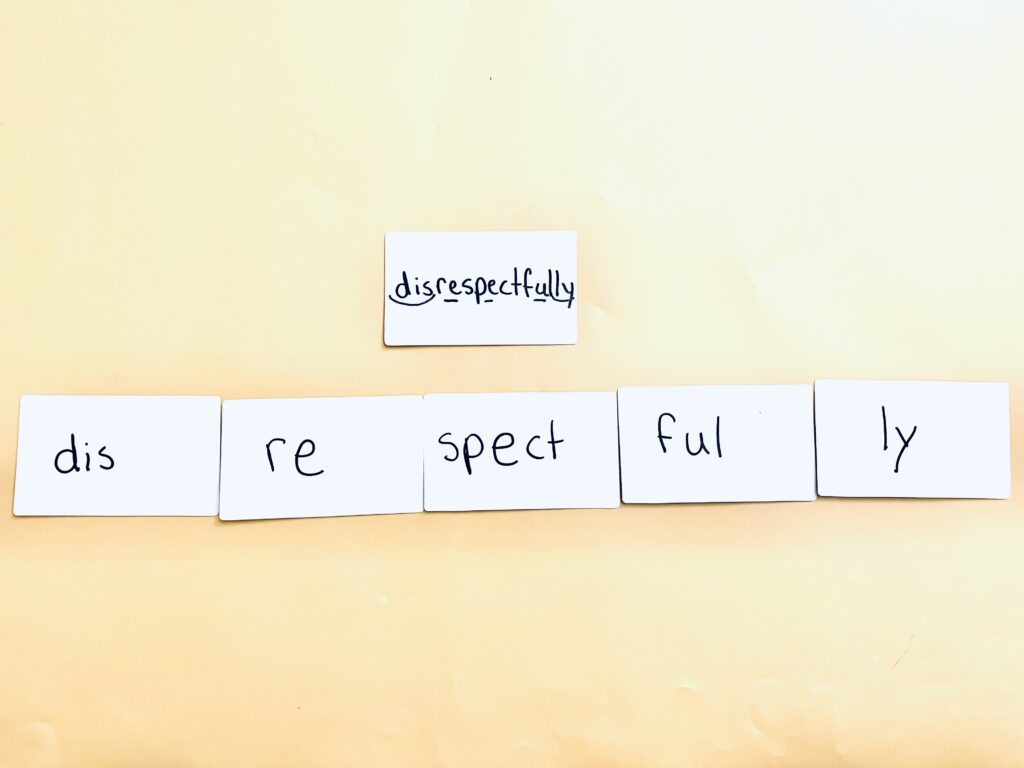

I use dry-erase notecards* from Amazon with my students for this purpose. These are the size of a regular notecard, but have been given a dry-erase surface for reuse. When I use them, every board represents a single syllable. Here are the steps I use with my students.

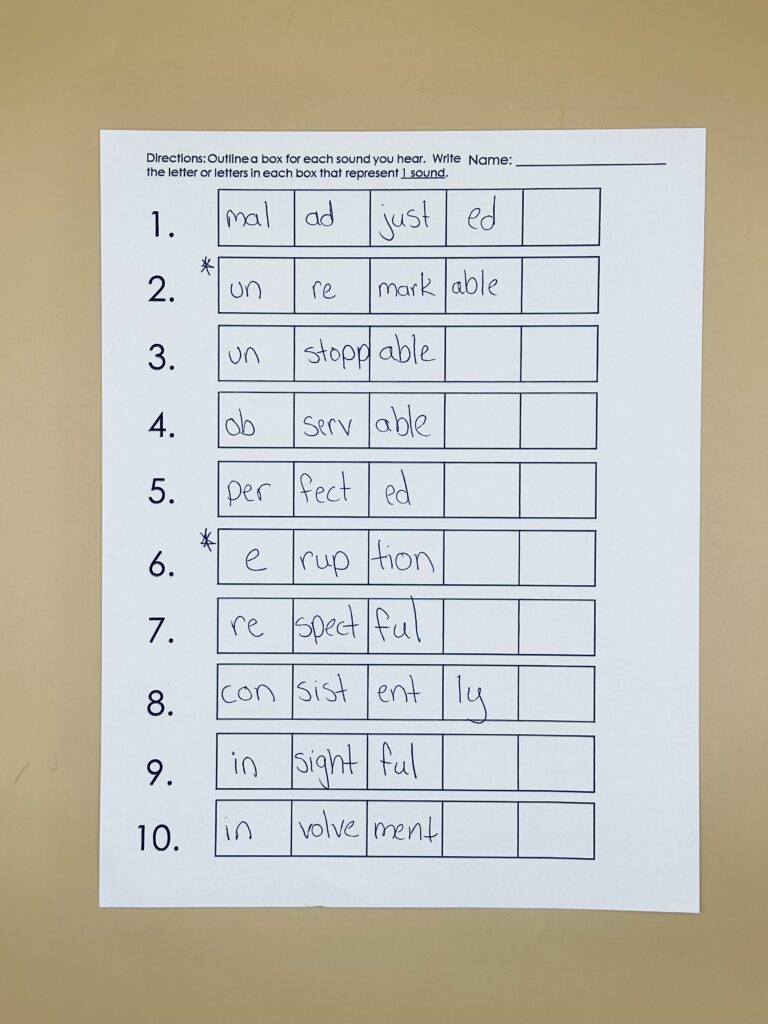

Step 1: Write down the entire word.

Step 2: Look for any prefixes/suffixes you know. Underline them.

Step 3: Underline vowels–make sure you keep vowel teams, r-controlled vowels, and magic e together.

Step 4: Count the lines for prefixes/suffixes and how many vowels you underlined. This is how many syllables you have.

Step 5: Pull down the prefixes, suffixes, and vowels.

Step 6: Use your knowledge about syllable types to finish splitting up the word.

The kids love getting to use the little dry erase notecards! I try to use words that either are related to the morphology we are learning (or have learned), or words that will be coming up in the text we are reading.

Morphology is the study of morphemes, or meaningful word parts. Because so much of our language is derived from other languages, we can learn a lot about word meanings by studying word parts.

English is made up 4 distinct layers: Anglo-Saxon, Latin, French, and Greek. All layers except for French have distinct affixes that we can teach.

When I am teaching morphology, I take the same approach I do when I am teaching basic phonics: my goal is to give students as many opportunities to read and write the morphemes as possible. If I expect children to orthographically map these words, they need to have a lot of practice with them. One day of introduction followed by homework and a test simply won’t cut it.

I start by reviewing morphemes in reading and spelling. We then introduce a new skill (not everyday), and work to practice that skill. Don’t overthink it–teach the skill and give them the practice they need to master it!

I have to be honest–teaching older students is hard. While teaching the primary grades is no easy task, the skills they need tend to be a lot more straight-forward than the skills our older children need. I can easily remedy a child who doesn’t read digraphs and blends, but when children are struggling to decode and understand multisyllabic words, I feel like that’s a whole new issue. And the answer isn’t always so clera-cut.

So, I hope that today I’ve given you some ideas on how you can better support those students. Give them access to the core, explicitly teach multisyllabic decoding and morphology. And above all else, give your kiddos the meaningful practice they need to become proficient.

*As an Amazon affiliate, I may receive a small commission on items purchased through my link. This is at no cost to you, and helps me to continue to provide weekly free content!

Share This:

Savannah Campbell is a K-5 reading specialist. She has taught her entire 12-year teaching career at the school she went to as a child. She holds two master’s degrees in education from the College of William and Mary. Savannah is both Orton-Gillingham and LETRS trained. Her greatest hope in life is to allow all children to live the life they want by helping them to become literate individuals.

Savannah Campbell is a K-5 reading specialist. She has taught her entire 12-year teaching career at the school she went to as a child. She holds two master’s degrees in education from the College of William and Mary. Savannah is both Orton-Gillingham and LETRS trained. Her greatest hope in life is to allow all children to live the life they want by helping them to become literate individuals.

Feeling overwhelmed with all the terminology out there? Want to know the key terms all teachers need to teach phonics? In this FREE Rules of English cheat sheet, you get a 5 page pdf that takes you through the most important terms for understanding English—you’ll learn about digraphs, blends, syllable types, syllable divisions, and move. Grab today and take the stress out of your phonics prep!