Share This:

The issue of phonemic awareness right now is HOT. I can’t go to Twitter or Facebook without seeing another heated argument over phonemic awareness. It can be overwhelming, it can get nasty (who would’ve thought, right?), and it can feel disheartening. I felt like I had just learned about teaching phonemic awareness and then I had to completely change my mindset. The truth, though, is a little more complicated. So today I’m going to give some insight into the arguments at hand, what the research says, and the implications for our instruction.

Phonemic awareness is a subset of phonological awareness. Where phonological awareness is the ability to manipulate any speech (think rhyming, counting words in sentences, clapping syllables), phonemic awareness deals specifically with individual phonemes. For example, can a child hear the word cat and tell you that the sounds are /c/-/a/-/t/? The different phonemic awareness tasks that can be addressed are segmenting, blending, adding, deleting (elision), and substituting. Adding, deleting, and substituting are often considered advanced phonemic awareness skills.

Let me start with this: no one is devaluing or underestimating the importance of phonemic awareness in becoming a proficient reader (Well, no one in the Science of Reading community). It is not up for debate. We know, and we have decades of evidence to support it, that phonemic awareness is absolutely critical for learning to read. In fact, along with letter-sound knowledge, phonemic awareness is the best indicator for how well a child will learn to read in the first two years of school.

But phonemic awareness is a hot topic in the Science of Reading world. The current debates circling phonemic awareness are as follows: the notion of teaching phonemic awareness to the “advanced” level and the amount of time we spend on phonemic awareness that is disconnected from print. I will examine both issues shortly.

Before moving on, however, I want us to keep in mind that phonemic proficiency is not the goal. Phonemic proficiency is a skill that will help us to achieve our reading goals. The National Reading Panel put it most clearly when they said, “Teachers should recognize that acquiring phonemic awareness is a means rather than an end. PA is not acquired for its own sake but rather for its value in helping learners understand and use the alphabetic system to read and write”(National Reading Panel, 2000, 2-6). So as we continue our discussion, let’s keep in mind our goal and continuously ask if our practices are helping to achieve those goals.

There are some very popular writers out there that insist children must have phonemic awareness to the advanced level in order to become proficient readers. Clemens et al state “the core of the argument is that ‘phonemic proficiency’… is necessary for establishing links between letter strings and pronunciations (i.e., orthographic mapping), and that an absence of such proficiency explains difficulties progressing beyond beginning stages of word reading” (2021, p.4-5). So is this true? Must children develop, almost along a continuum, from the most basic phonemic awareness tasks (segmenting and blending) to the more “advanced” ones?

The Clemens et al. article takes a lot of time to examine claims surrounding the efficacy of advanced phonemic awareness skills. The bottom line is this: segmenting and blending are the most important skills children need in order to become proficient readers and spellers. When learning to read, you are blending sounds together to make words. When learning to spell, you are segmenting sounds to write the corresponding graphemes.

There simply isn’t the evidence to support that children must have those advanced phonemic awareness skills to become proficient readers and writers. In some of the studies cited in the Clemens article, there were proficient readers who actually struggled with advanced phonemic awareness tasks.

Is it going to hurt children to practice oral-only advanced phonemic awareness tasks? Doubtful! But think about the amount of time you spend on any activity and, you guessed it, make sure it is aligned to your ultimate instructional goals. If you are spending 5 minutes a day deleting phonemes, that is 25 minutes a week. If we don’t have the evidence to support it is necessary to become a proficient reader, then I can’t justify spending that much time on it. But that doesn’t mean that I don’t address those skills.

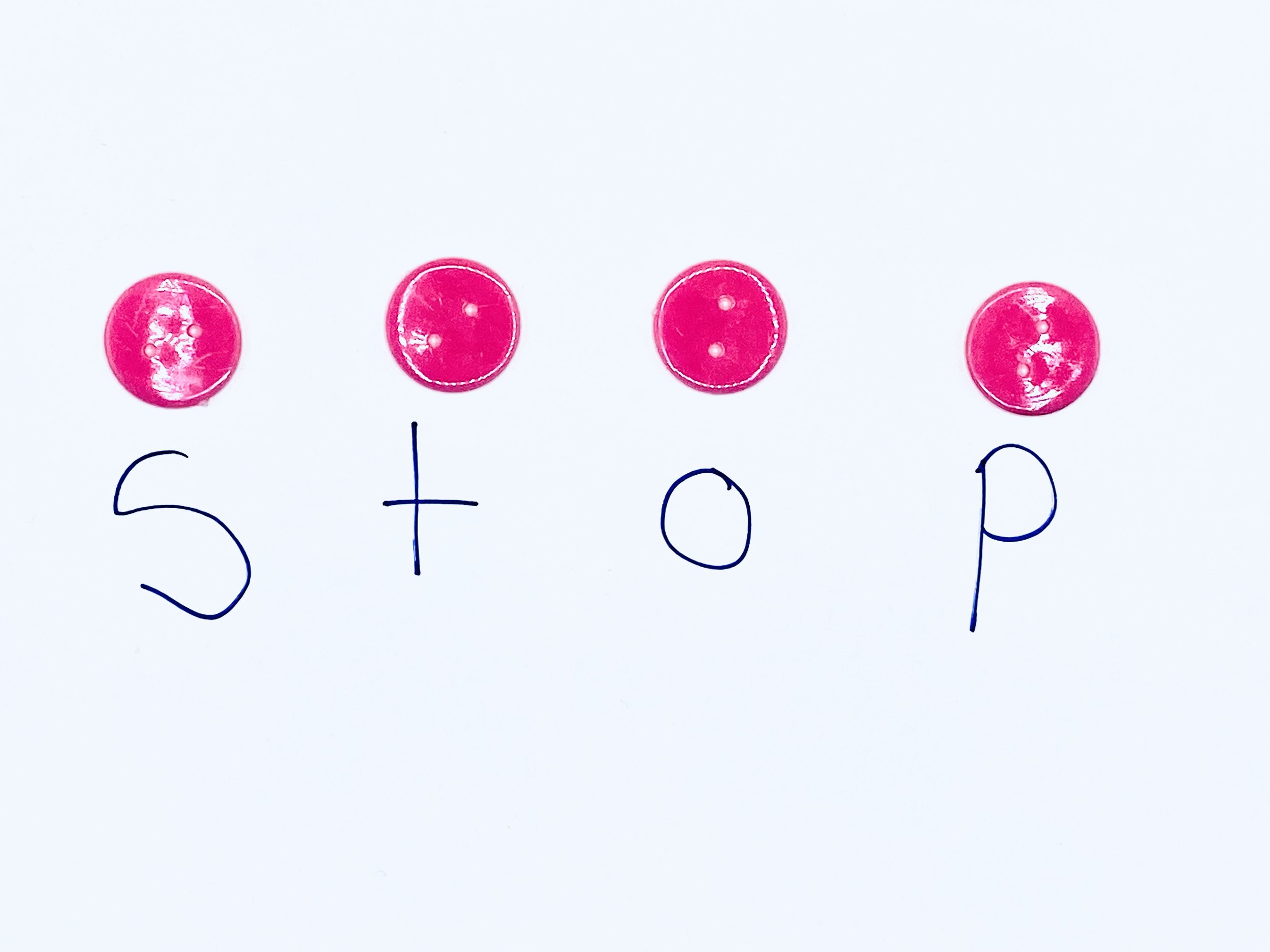

Let me give you an example of how I use some advanced phonemic awareness skills in my instruction. When I am teaching blends, I often see my students forget the second sound (stop is sop, snap is sap, etc.) So, I practice phoneme addition.

I will say a word like nap, then we will tap out the sounds. Next, I will ask them to add /s/ to the beginning and tell me the new word “snap.” We practice this several times, then we add letters into the mix and practice writing those words with blends.

So my conclusion? We don’t currently have evidence that says advanced phonemic awareness is a prerequisite for proficient reading. It may come about eventually, but it’s not there. Keep your goals in mind, and plan your instruction to match those goals for your children. Phonemic awareness should never be your end goal, but a means by which you get there.

To put it simply, phonemic awareness instruction is more effective when letters are involved. The National Reading Panel stated that “teaching children to manipulate phonemes using letters produced bigger effects than teaching without letters”(National Reading Panel, 2000, p.2-4). This does not mean that phonemic awareness without letters is ineffective, but that incorporating letters as much and as soon as possible gives us the largest impact.

If children do not yet know their letters, that does not mean that phonemic awareness instruction cannot happen. You CAN and you SHOULD start doing phonemic awareness instruction as soon as you can. There is no need to wait to address phonemic awareness until children know their letter names and sounds. The easiest way to get started is with phoneme isolation. For example, you say the word “jump” and a child tells you it starts with /j/. You could then move on to words with two and eventually 3 phonemes. Young children who don’t know their letters can still practice things like “Do mop and mom sound the same at the beginning?”

But the bottom line is that we can’t have phonemic awareness that isn’t connected to anything else we are doing. Phonemic awareness instruction that doesn’t connect to our other instruction reminds me of how I used to teach “word study” but then gave children leveled readers that included none of the skills I had just taught. In my opinion, however, that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t do phonemic awareness activities with manipulatives, or that oral-only phonemic awareness activities are useless. Especially for our youngest learners, phonemic awareness activities have to be done without letters because, well, they don’t know them.

Let me give you an example of how phonemic awareness and phonics can be married.

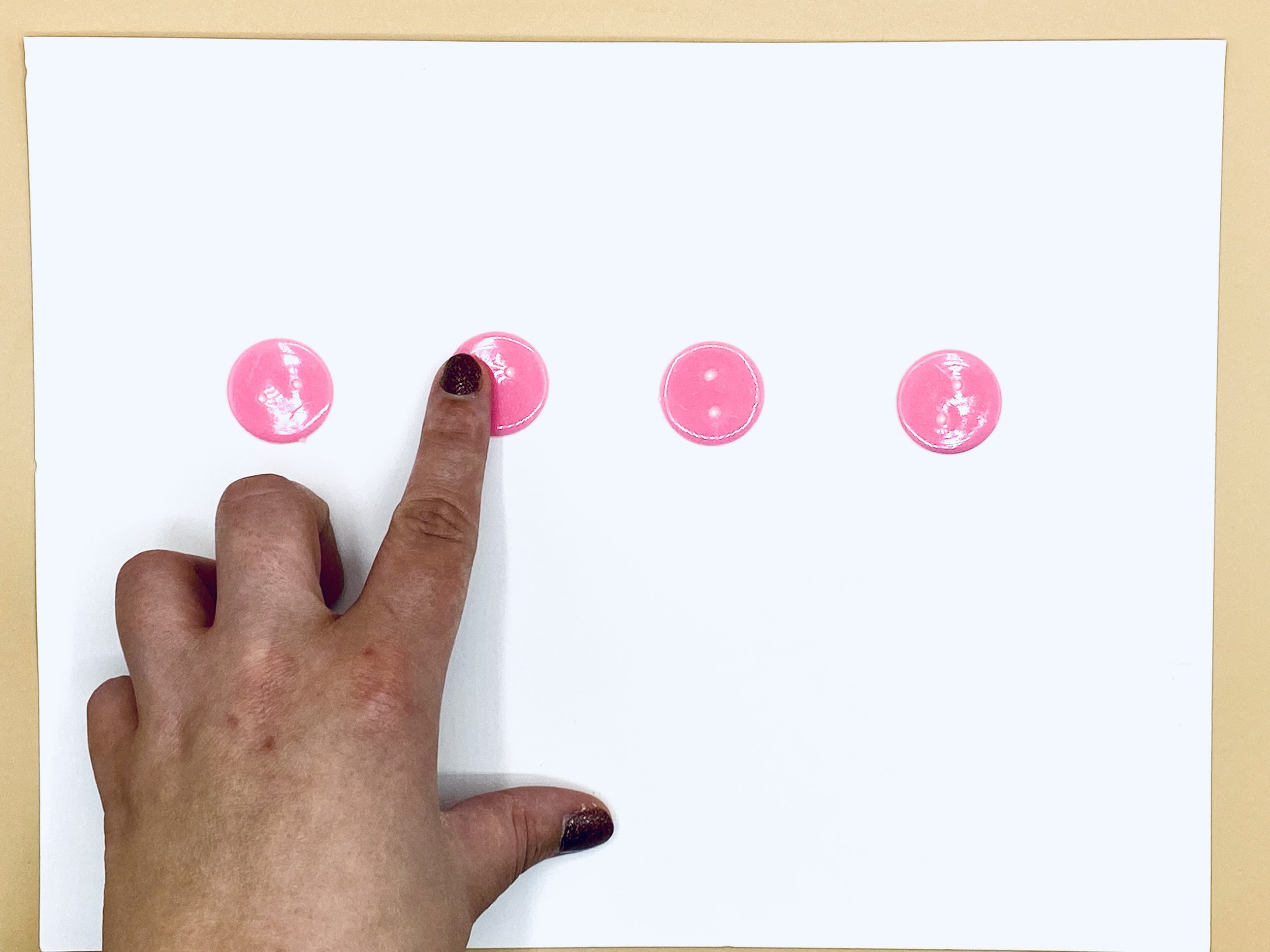

Say I am working on CVC words with my first graders. I could have a list of words that I want us to be able to read and spell. Our first activity could be to use pop-its (or cubes or blocks or….) to tap out the sounds in each of those words. We could then take the same list of words to tap and spell. If children don’t need to tap them, that’s okay too. This way, you can incorporate phonemic awareness with an authentic phonics experience to get you closer to your ultimate goal. The best part? You don’t need anything fancy to do this kind of instruction.

Many of us have purchased a phonemic awareness curriculum that doesn’t include printed text. You will not hear me tell anyone to throw it in the trash. Not by a long shot. There is still so much value in them. Just like you often have to tweak any reading curriculum to fit the needs of your students, you may need to tweak your phonemic awareness curriculum to better align with the rest of your instruction. The biggest factor to keep in mind, however, is that an oral-only phonemic awareness curriculum is not the only phonemic awareness instruction you should include daily.

I have a few ideas for how you can make your oral-only curriculum as effective as possible. For starters, I’d set a timer. Whatever amount of time you are comfortable with, just don’t go over it. Next, choose a few skills to use, instead of all activities every day. Lastly, incorporate letters as much as you can. A phonemic awareness curriculum can be a lifeline for a teacher or district that just doesn’t know how to start explicitly teaching phonemic awareness to their students. It has all the activities and words laid out for you. There is no shame in using a well-planned curriculum, and there are several great ones out there.

Before 2019, I would have struggled to tell you the definition of phonemic awareness. I would have struggled even more for a reason why I should care. Learning about the importance of phonemic awareness felt like the missing piece, the holy grail, and any other cliche “complete me” thought. It was what I was missing. I gobbled up every book I could get my hands on and started incorporating it everywhere. I thought that I needed to really emphasize that this was sound-only work. My mantra was very much “phonemic awareness can be done with your eyes closed.”

My biggest change has been that I now realize how important it is to incorporate letters as soon as possible. Learning to read is all about connecting speech to print. Understanding the speech sounds is great, but it does nothing for us as readers unless we can then bring them to the graphemes representing those sounds. Instead of spending 10 minutes on an oral-only phonemic awareness activity, I will spend a minute or two on oral-only phonemic awareness, and then build phonemic awareness into my phonics lessons. Instead of thinking I need to alter all of my phonemic awareness instruction, I’ve found myself making small shifts to gain a bigger impact for my children.

Whew, this one was a doozy. I’m going to tell you what I always tell myself—keep your goals in mind. When you think about how much instructional time you have, ask yourselve if the amount of time alloted is appropriate. Are you spending too much time on oral-only tasks, and not enough time connecting those sounds to letters? If you feel like you’re witnessing a pendulum swing in real-time, just know this: as practitioners we must always learn and grow. There will never be a time when we know it all. The best educators are the ones who continously prune and shape their practices for the sake of children. I see this as just another way we can grow and stay targeted for the sake of children.

Clemens, N., Solari, E., Kearns, D. M., Fien, H., Nelson, N. J., Stelega, M., … Hoeft, F. (2021, December 14). They Say You Can Do Phonemic Awareness Instruction “In the Dark”, But Should You? A Critical Evaluation of the Trend Toward Advanced Phonemic Awareness Training. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/ajxbv

National Reading Panel (U.S.) & National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (U.S.). (2000). Report of the National Reading Panel: Teaching children to read : an evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction. U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Share This:

Savannah Campbell is a K-5 reading specialist. She has taught her entire 12-year teaching career at the school she went to as a child. She holds two master’s degrees in education from the College of William and Mary. Savannah is both Orton-Gillingham and LETRS trained. Her greatest hope in life is to allow all children to live the life they want by helping them to become literate individuals.

Savannah Campbell is a K-5 reading specialist. She has taught her entire 12-year teaching career at the school she went to as a child. She holds two master’s degrees in education from the College of William and Mary. Savannah is both Orton-Gillingham and LETRS trained. Her greatest hope in life is to allow all children to live the life they want by helping them to become literate individuals.

Feeling overwhelmed with all the terminology out there? Want to know the key terms all teachers need to teach phonics? In this FREE Rules of English cheat sheet, you get a 5 page pdf that takes you through the most important terms for understanding English—you’ll learn about digraphs, blends, syllable types, syllable divisions, and move. Grab today and take the stress out of your phonics prep!