Share This:

Pretty regularly, the issue of blends comes up. Do we explicitly teach them, or not? With so many different sound-symbol correspondences to teach, is it really worth the time to teach blends? Today, I want to address what blends are, why we’re arguing, and why you really, really should be teaching them.

A blend is two or three consonants that are next to each other yet keep their individual sounds. For example, the st- in stop is a consonant blend, the scr- in scrape is a blend, and the -ct in act is a blend. In contrast to a blend, a digraph is when two letters make a single sound. For example, the ch- in chin, the th- in this and the -sh in wish are all digraphs.

I do not know of any research that is specific to teaching or not teaching blends. There are currently two camps around this argument—one side of the argument feels that teaching blends is a waste of time, while the other side (which includes me) believes it is essential for a majority of our students.

The argument against explicitly teaching blends is this: blends maintain their own sound, so they do not need any special instruction. If a child really knows s and t, then the st- in sticker shouldn’t present a problem. They will say that “blend” is a verb, not a noun.

When there are 250 graphemes in the English language, many people argue against spending the time to teach blends (since blends are multiple graphemes). You could spend an entire year if you teach each of the blends, and we just have too much ground to cover.

I disagree, and I’ve yet to hear an argument that convinces me we shouldn’t teach blends. The coarticulation that occurs with blends makes blends difficult to naturally acquire. Coarticulation is the subtle shift in pronunciation that happens when sounds are uttered in a sequence. A very good example of this is tr-. If you were to look at the word trap, we do not say /t/ /r/ /a/ /p/ and then get trap. It sounds more like a “chr” at the beginning. Say the word “act.” Do you distinctly hear the /c/ and /t/? For me, the sounds are muddied at the end, even if they are separate sounds

Some of our children will get blends without explicit instruction, but I want instruction that works for all children. And in my experience over the past 12 years with students, many children will not be able to accurately encode and decode words with blends without explicit instruction. If I were to just teach letter sounds and then move on to other graphemes, too many kids would be left to figure out coarticulation without help.

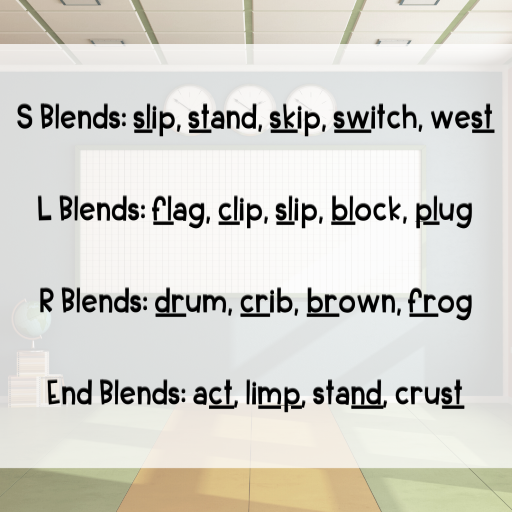

There are four distinct categories of blends—s blends, l blends, r blends, and end blends. We don’t have to spend the entire year teaching every individual blend: instead, let’s group them into those categories above. So, when I teach s blends, I’ll teach all of them within a week or so. The same with the remaining categories. The hardest blends for students to learn are the r blends because the coarticulation is so difficult. I save those for after s and l blends, and I often have to spend more time on them.

The best way to help students accurately decode and encode blends is by providing explicit modeling and practicing. I like to start with a CVC word, like nap. I ask students to tap it, often using manipulatives like cubes. Then, I will ask them to say nap, but add an /s/ to the beginning. They will then come up with “snap.” Don’t be discouraged if, on the first few times they are still saying words like “sap” instead of “snap.” Remember, it takes a lot of practice to become proficient with a new skill. Feel free to model the entire procedure from start to finish several times and then have your students copy what you have done.

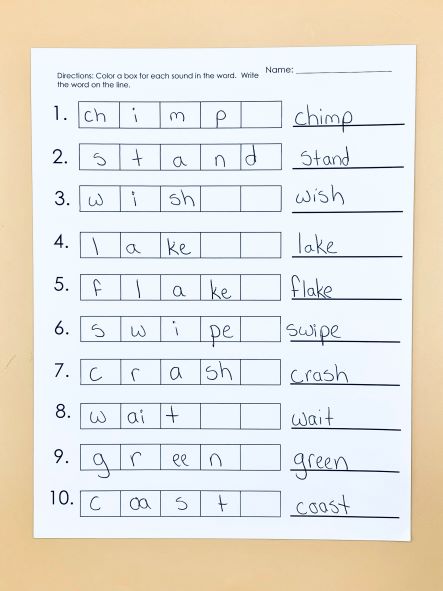

Sounds boxes are an excellent way to reinforce blends. Since each letter in the blend retains their individual sound, you can show this by having them use sounds boxes and putting each sound in a separate box. It makes an abstract idea very concrete for our students.

Make sure you are incorporating the phonemic awareness component to this, and not just focusing solely on the letters: some children need explicit instruction just to hear the sounds in a blend. Spending a minute or two each day practicing segmenting and blending words with blends is an extremely valuable instructional practice. You’ll be surprised how quickly children stop saying /s/ /a/ /p/ for snap and turn into children who are able to segment a word like stamp or crust with ease!

I know that I will not convince everyone that we should teach blends, but I really wish we would. If you even spent 3 weeks explicitly teaching blends, you will be able to reach so many more children than if you didn’t. It is only with EXPLICIT instruction that our children are able to acquire these skills. And since thousands and thousands of words include blends, I can’t leave it up to chance. What about you?

Share This:

Savannah Campbell is a K-5 reading specialist. She has taught her entire 12-year teaching career at the school she went to as a child. She holds two master’s degrees in education from the College of William and Mary. Savannah is both Orton-Gillingham and LETRS trained. Her greatest hope in life is to allow all children to live the life they want by helping them to become literate individuals.

Savannah Campbell is a K-5 reading specialist. She has taught her entire 12-year teaching career at the school she went to as a child. She holds two master’s degrees in education from the College of William and Mary. Savannah is both Orton-Gillingham and LETRS trained. Her greatest hope in life is to allow all children to live the life they want by helping them to become literate individuals.

Feeling overwhelmed with all the terminology out there? Want to know the key terms all teachers need to teach phonics? In this FREE Rules of English cheat sheet, you get a 5 page pdf that takes you through the most important terms for understanding English—you’ll learn about digraphs, blends, syllable types, syllable divisions, and move. Grab today and take the stress out of your phonics prep!