Share This:

Sometimes I feel like trying to learn about comprehension is just too much. Everyone seems so much further ahead than me, and then there’s just so many components to it. I want to be honest that this is an area where I have struggled for a few years, and I’m just finally getting to the point where I am comfortable enough sharing some of my learnings with you.

Today, I want to share some quick wins with you. Often when we get overwhelmed, we feel paralyzed and can’t act. I get it. I’ve been there too. If we don’t know where to start, we end up not doing anything at all. I want to give ALL teachers easy wins that will improve comprehension no matter the text you are working with. I’m not giving you everything you need to teach comprehension. Instead, I’m giving you some things you can do right now to improve comprehension immediately. Let’s keep learning even while taking action today.

Before I get to the tips, I want to discuss why comprehension is so dang difficult. For me, comprehension is hard because it changes with each text children have in front of them. Just because a child has solid comprehension with one text, that does not mean that the comprehension will transfer to a new text. Even as adults our level of comprehension varies: think about how easy it is for us to understand Colleen Hoover’s latest book and how hard it is to read a research article.

Comprehension really depends on your background knowledge about the subject and the vocabulary you know. If I tried to read a book about quantum physics, I would flounder because I don’t have any real knowledge of the topic and I don’t know much of the scientific vocabulary that would be required of me. (I literally have a quantum physics for babies BOARD BOOK that I still don’t understand.) Give me a book about Tudor England and I will demolish it because I have a deep understanding of that time period in history. Comprehension depends on so many factors, and that is why it is just so difficult.

But remember, difficult doesn’t mean impossible. And I have 5 tips for you that can help improve your comprehension instruction immediately.

Remember how we said so much of comprehension depends on our background knowledge? Well, if you don’t have a basic understanding of the world and how it works, then you really won’t have the background knowledge necessary to understand the texts that will be required of you in your educational and professional career. We MUST NOT REMOVE SCIENCE AND SOCIAL STUDIES FROM OUR CURRICULUM. When we do that, we are eliminating those huge topics that will teach our children about the world.

When teaching reading, try to pull in texts related to your science and social studies standards as much as you can. If you are teaching magnetism, see how many related texts you can find. You can share some in science class, but you can also work on comprehension with these texts in your ELA block. Furthermore, use a variety of texts around the same topic in small group. The more opportunities we give children to learn about a topic, the deeper their knowledge of that topic grows.

My favorite places for finding texts are Readworks and Newsela. Readworks is completely free and my primary source for finding texts. I love that I can search by topic, skill, grade level—basically any way you might want to search. Newsela provides news articles at different Lexile levels. So you can use the same text with a class, but alter it to make it easier or harder according to Lexile. It used to be completely free, but it now appears that you can only get limited access with a free account. It is still worth checking into!

We often expect children to read a passage and then answer comprehension questions. There is nothing wrong with expecting children to understand texts. What we need to remember, however, is that comprehension can fall apart at the paragraph and even the sentence level. If we only ask questions at the end, we may not realize that comprehension fell apart because of a single sentence or paragraph.

Let me give you an example. I had a student once who told me “Did you know that 10% of people die each year because of lightning strikes?” We were reading about electrical storms, and this was an obvious breakdown in comprehension. I asked her to read to me where she learned that, and the sentence said that 10% of people who are struck by lightning each year die. See how understanding is completely altered with a single sentence? There’s a big difference between 10% of everyone in the world dying each year due to lightning strikes, and 10% of the people who are struck by lightning dying.

So what does it look like to start at the sentence and ? For starters, always read the text before working on it with your students. This is not optional.

Next, think about which paragraphs and sentences might prove troublesome for your students. Make sure you stop at those places to discuss and confirm understanding. Something as simple as stopping to discuss a single sentence can ensure that students actually understand the text.

Teaching text structures means teaching the different ways a text is organized. We often talk about fiction and nonfiction, but it is much deeper than that. I prefer to think of it as narrative and expository. Under narrative, you can have fiction or nonfiction narratives (think biographies, books like Wilma Unlimited). Overall, I find that the narrative text structures are often taught very effectively.

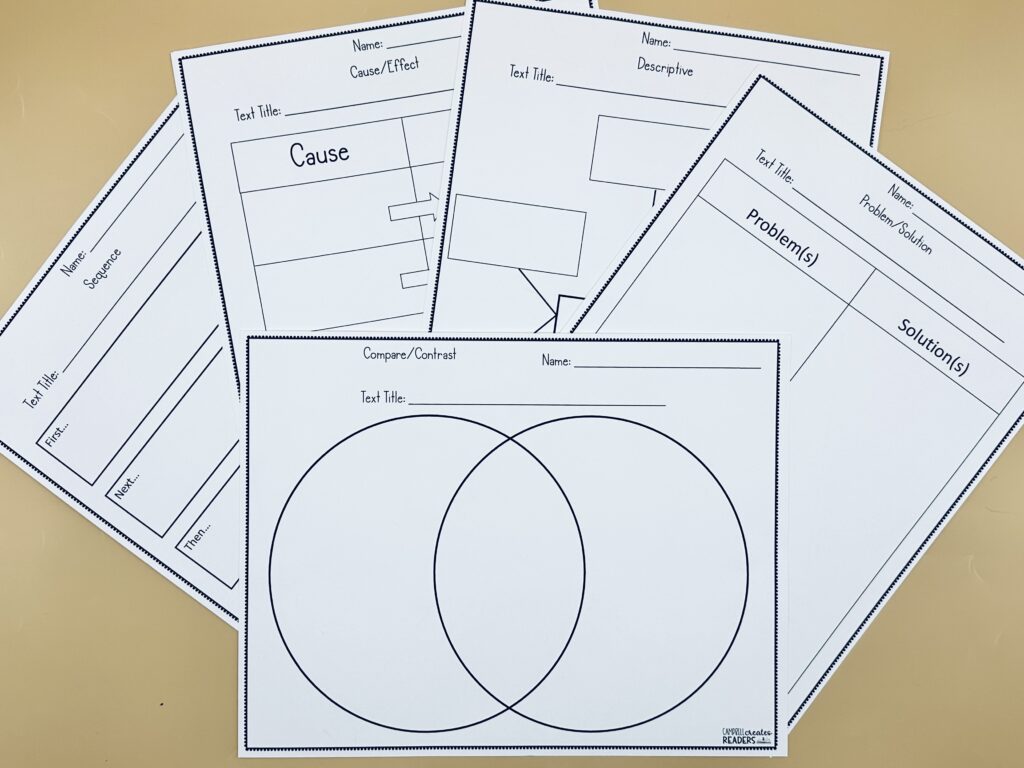

It’s the nonfiction text structures that don’t get as much attention. The nonfiction text structures I now teach are: description, sequence, compare/contrast, problem/solution, and cause/effect. We need to teach these different text structures so that our students can begin to anticipate what they will see in a particular text. Most of the time children know that in a story, they will come across a problem that needs solving. But do they know the key features of the other kinds of texts? Do they know that a descriptive text will tell them the attributes of something, a sequence text is step-by-step order, and a cause and effect text will teach them things that happen and why they happen.

I love what Nancy Hennessy says in The Reading Comprehension Blueprint*. She states, “text structure is considered a specific type of prior (or background) knowledge that skilled readers possess”(Hennessy, 2021, p.121). When we teach children to anticipate what is inside specific types of text, that’s background knowledge. They know the kind of information they will be looking for.

I think for 10 years I didn’t realize use graphic organizers effectively. I knew it was something I should use, but I didn’t really know how to do it. So I would find myself copying the graphic organizers and then half-heartedly filling them out. It felt more like an activity I felt I should do but didn’t understand how it would help my students.

Now, though, I get it. We teach text structures so that students can have a visual representation of that structure. How powerful would it be if children saw the same graphic organizer for cause and effect (and all the other structures) in kindergarten through fifth grade? It would just take them seeing the graphic organizer to understand the kind of information they will be retrieving from a text.

When we teach about pronouns, it often looks like this:

Mark went to the store. _____ went to the store.

And then we ask students to fill in the blank. But this is not the kind of work that will help move our children forward as readers. We need to teach pronouns in relation to how they help to tie a work together to facilitate understanding (aka, cohesive ties). Let me show you what I mean.

Look at this paragraph from Alice in Wonderland. There are 5 “its” in the paragraph. Can you name what each one is referring to?

Suddenly she came upon a little three-legged table, all made of solid glass; there was nothing on it except a tiny golden key, and Alice’s first thought was that it might belong to one of the doors of the hall; but, alas! either the locks were too large, or the key was too small, but at any rate it would not open any of them. However, on the second time round, she came upon a low curtain she had not noticed before, and behind it was a little door about fifteen inches high: she tried the little golden key in the lock, and to her great delight it fitted!

So what do each of the “it”s refer to? The first it is the table, second is key, third is key, 4th is curtain, and 5th is key. So across a single paragraph, one pronoun is used to reference 3 different subjects. THAT is the kind of thing that makes comprehension fall apart.

One easy think you can do is this: when you are reading texts, work with students to highlight the pronouns. Then, draw a line to what the pronouns are referring to. This is a way to help students see how it is all connected. It can be that simple!

Reading and writing are too often separated. We have our writing block where we write different kinds of texts, and then we have our reading block where we read different texts. But one powerful strategy we can employ is to start writing about what we are reading.

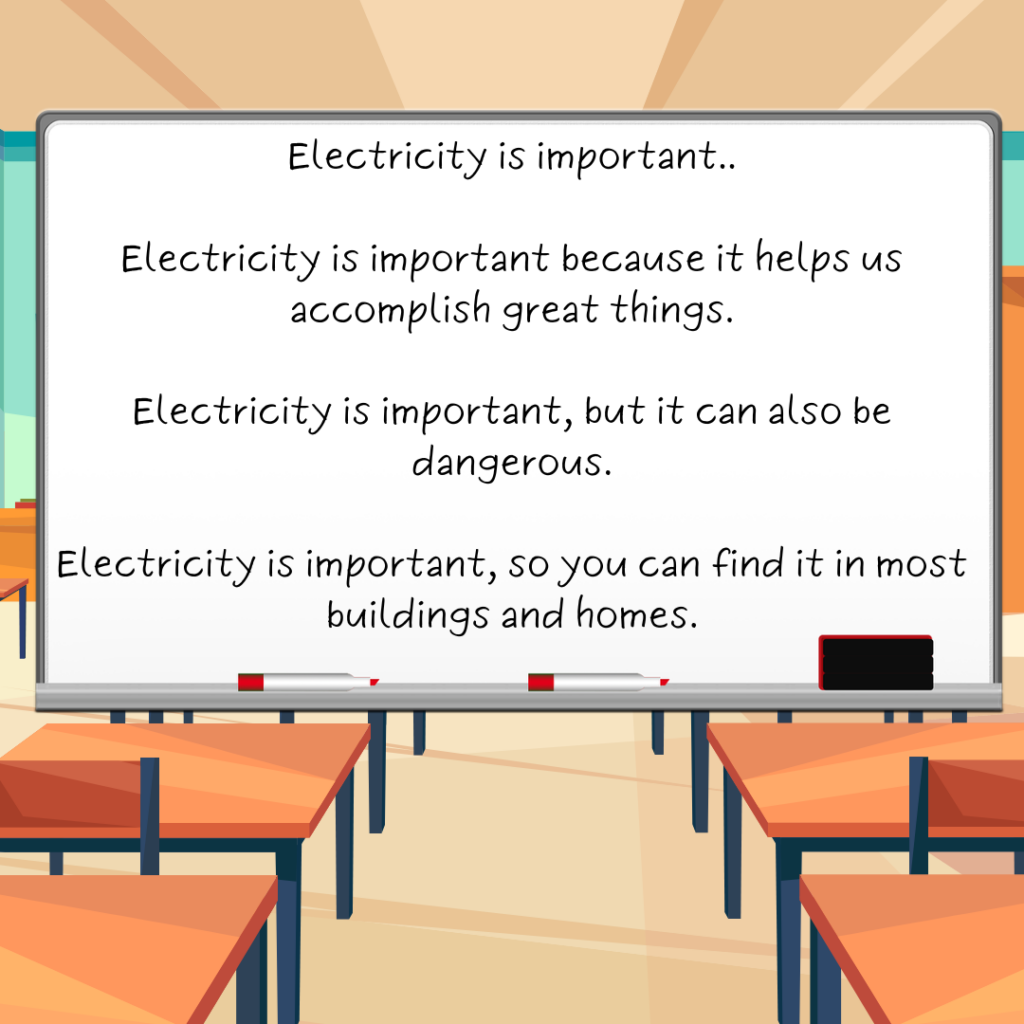

This is different from the world of writer’s workshop. We’re giving more guidelines, parameters, and explicit instruction. Writing about reading could be its own post, so today I jut want to share one strategy I learned from The Writing Revolution.* It is called “Because, but, so.”

Essentially, when you are reading about a topic, you give students the same sentence stem. You then ask them to create 3 separate sentences using the conjunctions “because,” “but,” and “so.” Let me give you an example.

Say I am learning about the founding father with my students. We have learned about the big key players, and we are now reading about Alexander Hamilton.

This could be my sentence starter:

Alexander Hamilton was an essential figure in the founding of America.

This could be your students’ potential sentences:

Alexander Hamilton was an essential figure in the founding of America because he was George Washington’s right-hand man and helped establish the first national bank.

Alexander Hamilton was an essential figure in the founding of America, but his legacy was overshadowed by his untimely death in a duel with Aaron Burr.

Alexander Hamilton was an essential figure in the founding of America, so he has been honored by having his face on the $10 bill.

Here’s the beautiful thing about writing about reading—you have to know about something to write about it. Think of the knowledge you need to possess in order to write those three sentences. Writing about what you have read helps to solidify your learning.

So there you have it—5 ways you can immediately improve comprehension with your students. You can begin incorporating all of these immediately and with minimal prep. I hope you’ve found something in here that you can take with you and use for your students. Feel free to let me know which one you’re going to start using!

*As an Amazon affiliate, I may earn a small commission for purchases made through my links. Your support helps fuel my content creation. Thank you for shopping and discovering amazing new resources with me. Also, I would never share anything that I don’t believe in with every part of me!

Share This:

Savannah Campbell is a K-5 reading specialist. She has taught her entire 12-year teaching career at the school she went to as a child. She holds two master’s degrees in education from the College of William and Mary. Savannah is both Orton-Gillingham and LETRS trained. Her greatest hope in life is to allow all children to live the life they want by helping them to become literate individuals.

Savannah Campbell is a K-5 reading specialist. She has taught her entire 12-year teaching career at the school she went to as a child. She holds two master’s degrees in education from the College of William and Mary. Savannah is both Orton-Gillingham and LETRS trained. Her greatest hope in life is to allow all children to live the life they want by helping them to become literate individuals.

Feeling overwhelmed with all the terminology out there? Want to know the key terms all teachers need to teach phonics? In this FREE Rules of English cheat sheet, you get a 5 page pdf that takes you through the most important terms for understanding English—you’ll learn about digraphs, blends, syllable types, syllable divisions, and move. Grab today and take the stress out of your phonics prep!