Share This:

I’ve made a lot of mistakes in my teaching. And the truth is, I’ll continue to make mistakes. There will never come a day when my instruction is perfect. The difference between my teaching today and my teaching five years ago, however, is that my errors are no longer the fundamental kind. I know that my knowledge of how children learn to read is solid, much more so than it was even a few years ago. So today, I’m going to talk about the big errors I used to make that I refuse to ever do again. I’ll save you from the ones I’m still making today.

My reading instruction revolved around leveled texts for 8 years. I remember trying to claim I used leveled readers, but I didn’t level students. But the truth is, the way I was using leveled readers was exactly that. Nicole was a level p, Anna was a level o, and Gail was a level y. My instruction revolved around trying to get students to level up. But y’all, these are children, not a video game, and the goal is not getting through all the levels.

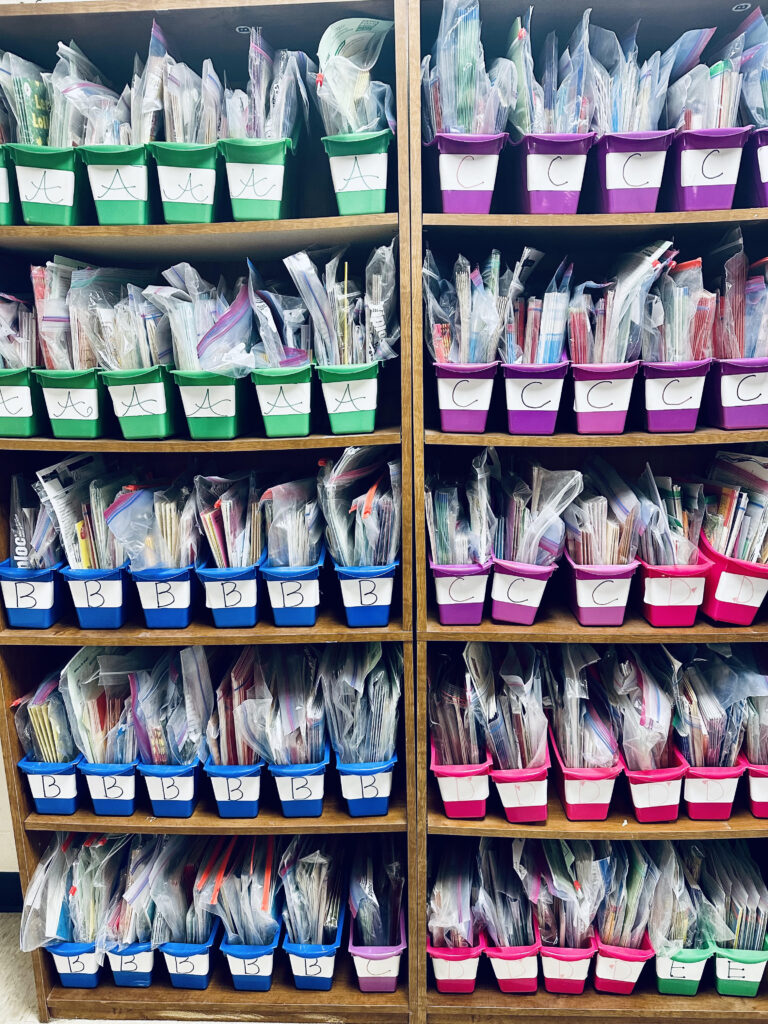

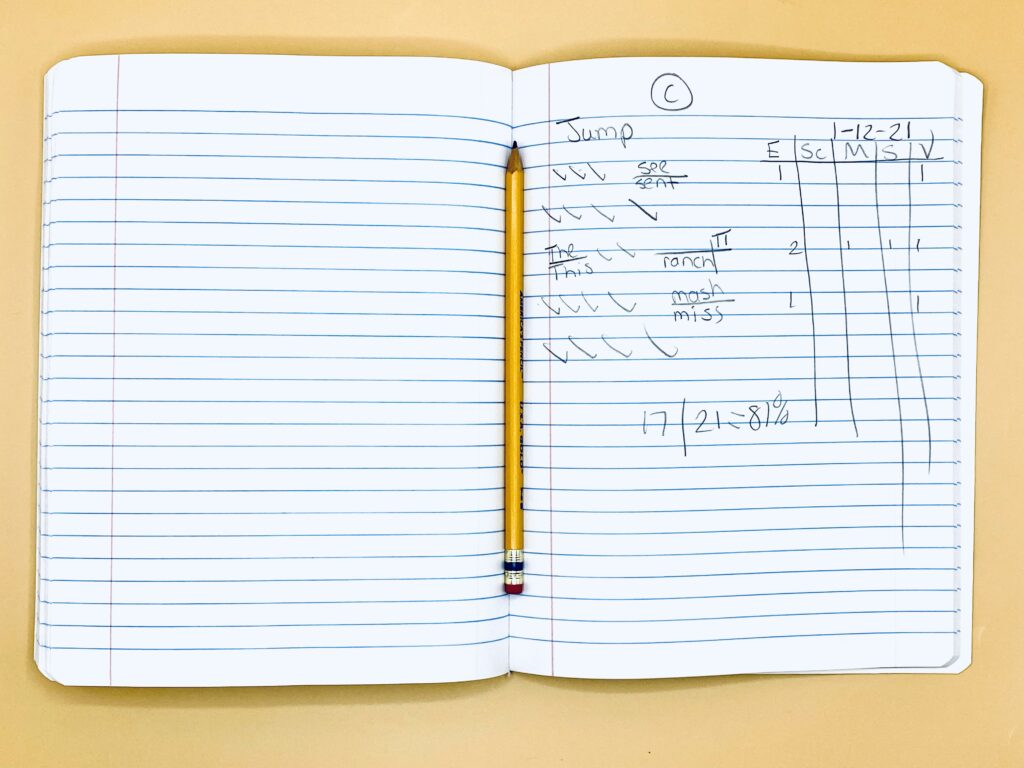

Now, I try to get specific about what phonics skills students are lacking, and I teach to those. In small group, I am using decodable readers to help build their automatic word recognition skills. I haven’t used a guided reading leveled text in years. Once students have control of most multisyllabic words, I will return to more traditional texts. BUT, I’m still not moving children through levels. I use my science and social studies standards to find appropriate texts to build background knowledge and vocabulary (I love texts from Newsela and ReadWorks). With fiction, choose texts that revolve around themes that you can build upon, like perseverance, kindness, etc. Because guided reading levels are not normed, standardized, or reliable in any way, I don’t see a reason to return to previous practices.

I remember telling parents that if children were reading and they made a mistake, as long as the word made sense, they shouldn’t correct it. When my children were writing, I would never point out misspelled words because I didn’t want to take away from their creative process by highlighting something as mundane as mechanics. I was always hesitant to critique or point out errors, fearing that I was humiliating my student.

But friends, remember that practice makes permanent, not perfect. The more times a child reads a word incorrectly, the more letters that are formed wrong, the longer the behavior persists. When children make an error, we are not berating them, mocking them, or humiliating them. If Sarah writes the letter h wrong, I will simply say “I love how hard you tried to make that letter Sarah. Let me show you the proper way.” Honor the child but correct the mistakes so that they can improve.

There’s a graphic going around about reading 20 minutes a night. I know because I used to send it home every year. At its core, the graphic suggests that those students who read at least 20 minutes a day do the best on standardized tests. I wish it were that simple. I used to believe it was a simple as this. If it were as easy as reading 20 minutes a day, we could easily eradicate illiteracy in this country. But although children who read the most do perform the best, simply assigning reading has not been shown to improve reading scores. (If you want to learn more about this, see the National Reading Panel’s subreport on fluency.)

I cringe when I think about all the parent-teacher conferences I had where I handed out that graphic. I told parents that their kids just hadn’t found a book they loved yet, that they needed to be reading more at home. Looking back, it must have been so insulting to those parents. Some of these parents were reading to their kids everyday since they brought them home from the hospital, and their kids still aren’t performing well. We cannot just assign reading and expect children to perform better. We have to actually teach children to read AND give them copious amounts of practice in texts that they can decode.

When I taught fourth grade, my students had about 30 minutes of independent reading a day. My classroom library had over 100 boxes of books with thousands of total books. It was a free-for-all, choose-what-you-want, just stay quiet and look busy kind of ordeal (But they were living readerly lives, which I thought was the most important thing). What’s worse? When I taught first grade, I also had them read independently for about 30 minutes a day. Like I said above, I really thought it was just as simple as giving children time to read.

But if a child cannot read, then just giving them more reading does not move them forward. Kindergarten and beginning first grade students are not expected to be reading on their own yet, so using long periods of precious instruction time for them to pretend to read is not beneficial. As students grow older, independent reading may be appropriate. I often ask students to read/reread a certain text for me, then let them choose what they want to read afterwards. I just want us to always think about what students are doing when they are not with the teacher, and make sure the activity is the most beneficial. Furthermore, any independent reading must be filled with actual reading, not pretending.

Ok, this one hurts. This one feels personal. And this one might be the hardest one to accept. But, the bottom line is this: if our children aren’t making progress, we must look at our own instruction first. Have you ever had a child who wasn’t making progress and you thought, “there must be something wrong with this kid?” Me too. I’m ashamed, but I did. What I should’ve said was, “This kid isn’t making progress, what can I do to help them improve?”

I had to change my mindset. We know that with proper intervention and first instruction, 95% of children can learn to read on grade level. It is exceptionally rare that you will have a child who cannot make progress with proper instruction. Before we put a child up for child study, we must make sure the child has had the appropriate first instruction and intervention. This is not a “wait and see” approach: I am advocating that before we ask if a child has a learning disability, we ask if there is something more WE need to do to ensure that child can be successful. We are not waiting: we are actively altering our instruction to give those children what they need.

5 years ago, I wouldn’t recognize the teacher or the person I am today. These things I used to do were literally a part of my identity. I tried everything I could to get my children to become readers, except actually teach them how to read. Looking at this list, these are habits I’m glad to say goodbye to. In the past few years that I have let go of poor instructional practices, I’ve seen more growth in intervention students that I ever thought possible.

Do any of these items resonate with you? Have you also had to let go of some of these practices?

Share This:

Savannah Campbell is a K-5 reading specialist. She has taught her entire 12-year teaching career at the school she went to as a child. She holds two master’s degrees in education from the College of William and Mary. Savannah is both Orton-Gillingham and LETRS trained. Her greatest hope in life is to allow all children to live the life they want by helping them to become literate individuals.

Savannah Campbell is a K-5 reading specialist. She has taught her entire 12-year teaching career at the school she went to as a child. She holds two master’s degrees in education from the College of William and Mary. Savannah is both Orton-Gillingham and LETRS trained. Her greatest hope in life is to allow all children to live the life they want by helping them to become literate individuals.

Feeling overwhelmed with all the terminology out there? Want to know the key terms all teachers need to teach phonics? In this FREE Rules of English cheat sheet, you get a 5 page pdf that takes you through the most important terms for understanding English—you’ll learn about digraphs, blends, syllable types, syllable divisions, and move. Grab today and take the stress out of your phonics prep!